Valentyn Odnoviun. Two Creative Circles: Intersections among Lithuanian and Kharkiv art photographers from the late 1960s until 1980s

The essay in Lithuanian is available at Literatura and Menas.

Many interesting connections and inspirations took place from the late 1960s until the 1980s among selected art photographers of the unofficial Vremya group from Kharkiv, Ukraine, and members of the officially supported Society of Art Photographers of the Lithuanian SSR. In 2015 I found out that Jury Rupin, one of the founders of the Vremya group, moved to and lived in Lithuania for around twenty years. Already in Lithuania, he wrote Photographer’s Diary,1 Luriki,2 and A Photographer’s Diary in the Archives of the KGB,3 in which he revealed information about the history of the Vremya group, its members’ activity, and partially described their intersections with and inspirations by the Lithuanian colleagues. But what was the context in which these two creative circles emerged, and how did these intersections influence the development of art photography in both countries?

At that time, art photographers existed within the Soviet system which practiced censorship, stressed conformity, and propagated an officially approved ideology. As creative individuals, they were often challenged by these factors and resisted against them to various degrees and in different ways as they expressed their own creative visions, joining the shift to change the photographic medium.

By the late 1960s, photography was no longer regarded as primarily documentary and started to be recognized as an art form in the West. Photography also came to be considered as art in the Soviet Union and was influenced by major European tendencies through fellow Socialist bloc countries, such as Poland and Czechoslovakia. However, it was practiced under more restrictive conditions of the Socialist Realism, the only officially approved Soviet aesthetics.4

Lithuania played a leading role in the evolution of photography in the Soviet Union. The Society of Art Photographers was founded in Vilnius in 1969, establishing a new form of creative institution, which, among other activities, aided the development of art photography by staging exhibitions, seminars, and assisting with participation in foreign competitions.5 Lithuanian photographers were able to stretch boundaries in some cases through strategically and pragmatically maintaining relations with the party and the government, thus allowing them to improve conditions for their creativity more openly and on a larger scale in pursuing their photographic aims.6 This society was the only one of its type in the whole Soviet Union until 1989 and attracted photographers from different republics. In the early 1970s, as Jury Rupin mentioned in his writings, the words 'Lithuanian photography' also had a magical meaning for Kharkiv photographers, who always searched for well-known Lithuanian names in the Soviet photography periodicals.7 The preference was given to less self-censored and more creative photographers such as Vitas Luckus, Vitalijus Butyrinas, and Aleksandras Macijauskas. Another Kharkiv photographer, Evgeniy Pavlov mentioned that Luckus 'pushed' his colleagues in the direction of wide-angle photography8, but Kharkiv photographers moved even further, applying wide-angle to their so-called 'Blow Theory'9 and created panoramic 120° shots for their needs.

The Vremya group was founded by Jury Rupin and Evgeniy Pavlov in Kharkiv, Ukraine, in 1971, and included the most creative members of the Kharkiv photo club such as Boris Mikhailov, Oleg Malyovany, Gennadiy Tubalev, Oleksandr Suprun, Oleksandr Sitnichenko, and Anatoliy Makiyenko, who joined the group later.10 Being unofficial, the group did not have funding and was not able to publish its own catalogs, or to have sponsored exhibitions, but operated more on the margins of society, which is reflected in their selected subject matter and styles. Paradoxically, the absence of state support freed them from self-censorship and conformity and as a result, Kharkiv photographers were more often summoned to the KGB to explain their activities. In contrast, self-censorship affected the works of some Lithuanian photographers, which influenced their styles and topics. Despite such organizational differences, the Vremya group functioned in a somewhat analogous way to the Society of Art Photographers, which brought together the core of the innovative photography scene, encouraged the exchange of artistic approaches, and supported each other’s initiatives.

Having no special place for group gatherings, Kharkiv photographers met at their apartments or at the regional photography club, where they had discussions with other club members. Such 'amateurish' places as photo clubs organized for the masses, became some of the first places for artistic growth and development. Communication and common discussions of works of different photographers were the most important activity. In 1970—1971, somebody brought to the Kharkiv photo club a part of Luckus’s Pantomime series printed on large format high-quality paper, this event was later mentioned in Jury Rupins’ Photographer’s Diary.

Performative Pantomime series captured actors of Kaunas pantomime troupe, impressed photo club members by its technological features and particularly artistic use of a photographic medium. These photographs were instantaneously recognized as art photography.11 The actors were extracted from their theatrical environment and were placed into the context of staged Soviet reality. Kharkiv photographers saw a like-minded person in Vitas Luckus and his Pantomime revealed “other” photography which served as a trigger for their creative experiments. The next year Evgeniy Pavlov, being partially inspired by Luckus’ Pantomime, created his series Violin, in which he depicted naked Kharkiv hippies near a waterfront. A violin that one of the hippies brought with him unintentionally became the main subject of the series. The manifested hippies’ desire to be closer to nature, to be a part of it, and to seek freedom of expression, was in a way a protest against the Soviet lifestyle. The namesake photo book, published in 2019, includes the original versions of some photographs, made as vertical panoramic shots.12 However, back in the 1970s, only more 'traditional' cropped images were presented, and in 1973, the Violin was published in the Polish magazine Fotografia.13

This series inspired Jury Rupin to create the Sauna, one of his most prominent projects, in which he depicted naked bodies of men in the bathhouse. Photographs were taken not outside but in a closed environment. The shots with a longer exposition time captured the dynamism, some body parts left unfocused. However, it is not clear if Rupin did it on purpose or accidentally. Although men’s genitals are visible in the images, these photographs were not banned by Soviet authorities, since they were taken in a bathhouse, a proper communal place for being naked and considered to promote a healthy lifestyle of a socialist proletariat.

© Vitas Luckus. Pantomime series, 1968-1972. Courtesy: Šiaulių „Aušros“ muziejus

© Evgeniy Pavlov. Violin series, 1972. Courtesy of the author

© Jury Rupin. Sauna series, 1972. Courtesy: Vasa Project / MOKSOP

Luckus opened freedom of action for Kharkiv photographers and Pavlov later developed this freedom on a larger scale, including naked male bodies to his work, and Rupin managed to avoid censorship. All three series display dynamism, but each in a different manner, and include some depictions of the naked body. They have somewhat similar ideas of performativity but expressed through different presentation methods.

Although Kharkiv photographers knew about Vitas Luckus already in the early 1970s, Jury Rupin only got acquainted with Luckus personally in 1975. This happened accidentally during one of his trips with Boris Mikhailov. They met Luckus and his wife Tatjana Luckienė in Sudak (Crimea, Ukraine). During that trip, they spent a lot of time talking about photography and soon became friends. Later, Boris Mikhailov gave Luckus an album of photographs from that trip.14 Another short meeting happened in Vilnius after Rupin and Mikhailov visited Nida and Klaipėda. During their second trip to Lithuania, Mikhailov and Rupin, thanks to Luckus, met other famous Lithuanian photographers Rimantas Dichavičius and Vitalijus Butyrinas. Before that, Kharkiv photographers already knew photomontages created by Butyrinas and were inspired by him as well.15

Photomontage was popular among not only European but Soviet photographers as well and was practiced by many artists from the late 1960s until the 1990s. Vitalijus Butyrinas is the most successful in the use of this technique. Also, it was used by Ukrainian-born Latvian photographer Vilhelms Mihailovskis and Polish photographer Zofia Rydet (born in Stanisławów, Poland, now Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine), who created a cycle of montages titled A World of Feelings and Imagination (1975—1979). Photomontages of Butyrinas present a reflective mood that includes either scenes from nature or female bodies and shows a distinctive combination of the surreal and the romantic and the real, which was considered a new approach to photography in the 1970s.16 Among Kharkiv photographers, photomontages and collages were created by Oleg Malyovany, Oleksandr Suprun, Jury Rupin, and Evgeniy Pavlov.17

Oleksandr Suprun selected this technique as the main one for his artworks.18 As was mentioned in Rupin’s diary, he became inspired by the work of Butyrinas but the mood of his photomontages differs from that of Butyrinas’. Suprun’s photomontages were created from collected components of different objects, people, skies, etc. It took months to collect the necessary parts. Also, he copied images of people or objects and often mirrored them in his work. He concentrated mainly on relevant social themes of that time. Despite all technical manipulations, the style of his montages reminds rather of reportage-style photography, than of the creation of 'other worlds,' compared to the works of Malyovany, Pavlov, Mihailovskis, Rydet, or Butyrinas.

© Oleksandr Suprun. Beacon Carer, 1977. Courtesy: Vasa Project / MOKSOP

© Vitalijus Butyrinas. Cottage by the sea, 1983. Courtesy of the author

© Vitalijus Butyrinas. Music. Neringa series, 1983. Courtesy of the author

Also, Suprun’s series Markets reminds of photographs made at rural markets by Lithuanian photographer Aleksandras Macijauskas, who photographed markets with a wide-angle lens, close-ups, and ironic outlook. In A Photographer’s Diary in the Archives of KGB, Rupin mentioned how members of the Vremya group talked with Suprun concerning the topic of markets that had already been explored by Aleksandras Macijauskas. Indeed, some of Suprun’s works recall photographs made by Macijauskas, but the main difference is that in the case of Suprun, the 'reportage' is, in fact, a montage created from several images. Suprun’s markets present scenes not actually photographed, but accurately created by the author.

© Aleksandras Macijauskas. Prienai, 1971, Lithuanian village markets series. Courtesy of the author

© Oleksandr Suprun. Markets series, 1988. Courtesy: Vasa Project / MOKSOP

Another technique practiced by photographers from Lithuania and Kharkiv was isohelia. This method was invented in Lviv in 1936 by Witold Romer and was based on the process of copying a photographic negative onto a high contrast photo paper. The reduction of the tonal range into several brightness intensity areas made the isohelia technique useful in scientific research but was appropriated for artistic needs as well.19

© Oleg Malyovany. The age of beauty, 1973. Courtesy: Vasa Project / MOKSOP

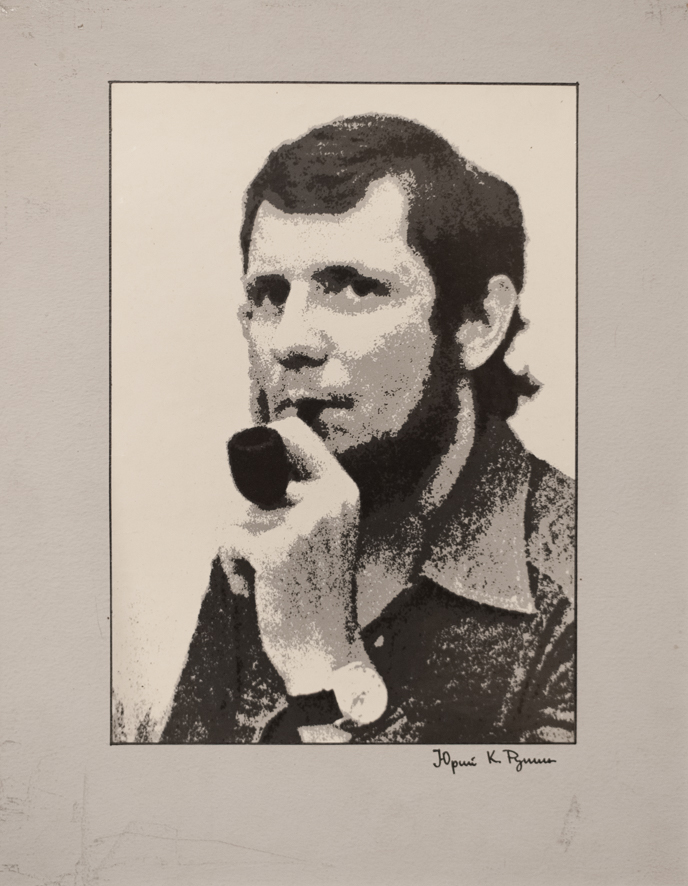

Among Lithuanian photographers, isohelia was practiced by Povilas Karpavičius, already in the late 1930s and Rimgaudas Maleckas. Karpavičius later advanced the technique to produce isohelia works in color. In 1957, he presented his works at the international exhibition in Wroclaw, Poland, being the only photographer from the Soviet Union. Povilas Karpavičius also shared his knowledge and photographic techniques with the next generation of Lithuanian artists, including Vitas Luckus, Aleksandras Macijauskas, and Vitalijus Butyrinas. Later, isohelia reached Latvia, where it was used mainly by Valters Jānis Ezeriņš. In Kharkiv, it was practiced mainly by Oleg Malyovany from the mid-1960s, who later taught Jury Rupin this technique. Rupin made portraits of his friends using this technique, including a portrait of Vitas Luckus.

© Jury Rupin. Portrait of Vitas Luckus. Reproduction by Valentyn Odnoviun. Courtesy: Jury Rupin family

Photomontage, collage, and isohelia were primarily regarded by the Soviet authorities as too formal. Naturally, they were a platform for experiments with a photographic medium in search of new ways of expression.

Later, photographers developed a new visual language, in which the idea, concept, prevailed over the form. Mikhailov’s conceptual approaches considerably influenced the next generations of artists, including Lithuanian photographers Virgilijus Šonta, Remigijus Pačėsa, and Alfonsas Budvytis. Also, the project of Boris Mikhailov Unfinished Dissertation presents some intertextual references to the Lithuanian photographers Algirdas Šeškus, Vytautas Balčytis.20

© Uladzimir Parfianok. Evgeniy Pavlov in Nida, 1987. Courtesy: Evgeniy Pavlov

Evgeniy Pavlov made his trip to Lithuania only once. He visited the Nida Photography Symposium in 1987, where he became friends with Belarusian photographer Uladzimir Parfianok. The main interactions between Kharkiv photographers with like-minded Lithuanian colleagues ended abruptly in 1987, after Vitas Luckus tragic death.

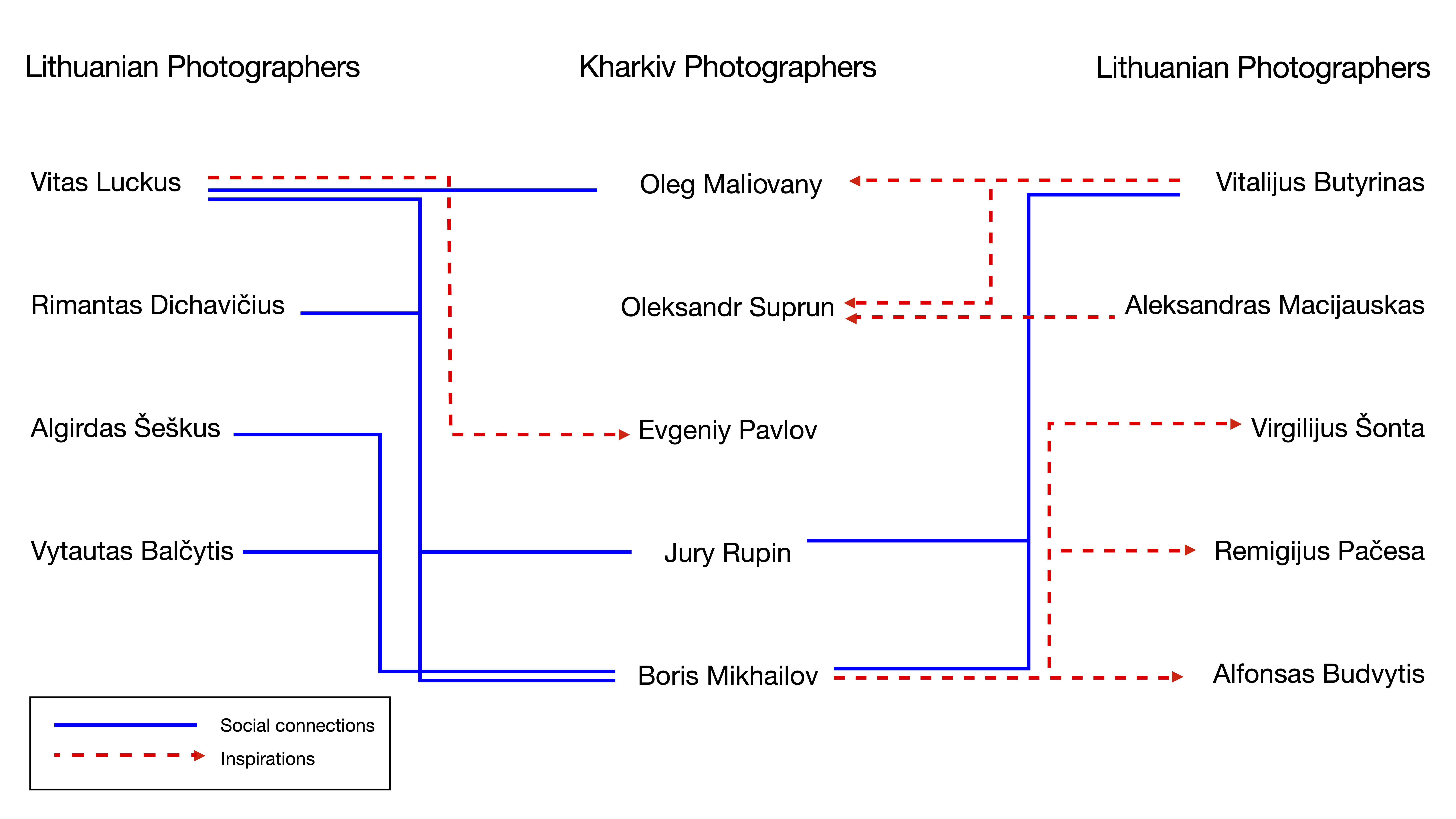

13. Scheme illustrating social connections and mutual inspirations among Kharkiv and Lithuanian photographers

Being produced in separate locations, the works of Ukrainian and Lithuanian photographers reflect differences in the political and cultural environments, specific to those places, along with some common features, occurred due to their interactions. These works serve as examples of how art develops through a mysterious combination of personal inspirations from one artist to another, as well as through the absorption and application of common major trends.

The essay was written for the project Kharkiv School of Photography: from the Soviet censorship to new aesthetics, сommissioned by the Ukrainian Institute for the Ukraine Everywhere program

Valentyn Odnoviun (b. 1987). Lithuanian art photographer and art historian. Ph.D. student at the Lithuanian Culture Research Institute, member of the Lithuanian Association of Art Photographers.

Sources:

- Рупин, Юрий, Дневник фотографа, Самиздат;

- Рупин, Юрий, Лурики, 20.08.1989—9.04.2005, Самиздат;

- Рупин, Юрий, Дневник фотографа в архивах КГБ, Самиздат;

- Cotton, Charlotte. The Photograph as Contemporary Art, 3rd edition, London: Thames & Hudson, 2014, 256 p., ISBN: 9780500204184;

- Matulytė, Margarita, Uzurpuota realybė: lietuvių fotografijos sovietizavimo procesai ir kolizijos (Usurped Reality. The Processes and Collisions of the Sovietization of Lithuanian Photography), Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis, t:58: Menas kaip socialinis diskursas, 2010, p. 71- 93, ISBN: 9786094470011;

- Michelkevičius, Vytautas. The Lithuanian SSR Society of Art Photography (1969-1989): An Image production Network. Vilnius: Vilnius Academy of Arts Press, 1st edition 2011, 416 p., ISBN: 9786094470332;

- Рупин, Юрий, Дневник фотографа, Самиздат;

- Рупин, Юрий, Дневник фотографа, Самиздат;

- Pavlova, Tatiana, Late 1960's to 1980s: The Vremya Group’s Time, in: Kharkiv School of Photography: Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics. 1970–1980s, VASA Project;

- Pavlova, Tatiana, Late 1960's to 1980s: The Vremya Group’s Time, in: Kharkiv School of Photography: Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics. 1970–1980s, VASA Project;

- Рупин, Юрий, Дневник фотографа, Самиздат;

- Pavlov, Yevgeniy, Violin, Rodovid: Ukraine, 2018, 128 p., ISBN: 9786177482269;

- Fotografia,1973 (1), Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Arkady, p. 10-11;

- Vitas Luckus. Biography, Edited by Matulytė, Margarita, Luckienė-Aldag, Tatjana, Vilnius: Lithuanian Art Museum, Kaunas Branch of the Union of Lithuanian Art Photographers, 2014, 248 p., ISBN: 9786094260568;

- Гайжутис, Альгирдас, Фотохудожник Виталий Бутырин, По материалам книги

- Гайжутис, Альгирдас, Фотохудожник Виталий Бутырин, По материалам книги Виталия Бутырина Избранные фотографии, Москва: Планета, 1991, Mi Kron;

- Kharkiv School of Photography: Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics. 1970—1980's, Video interviews, VASA Project;

- Сандуляк, Алина, Харьковская школа фотографии: Александр Супрун, Art Ukraine, 30.07.2018;

- The History of Polish Photography, Culture.pl, 04.06.2002;

- Narušytė, Agnė, The Aesthetics of Boredom. Lithuanian Photography 1980—1990, Vilnius Academy of Arts, 2010, 352 p., ISBN: 9789955854968