Alina Sanduliak. Kharkiv School of Photography: The Game of the Everyday

Whereas in Europe and America of the 1960s through 1980s, photographers were free to choose any aspect of the everyday to document, the Soviet Union required long, hard thought before engaging in street photography and angle experiments. “Kharkiv School of Photography: Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics” is a project that allows us a clearer understanding of how late Soviet Ukrainian photographers saw the socialist everyday.

Art history has the concept of 'genre art.' It pertains to everyday narratives, stories of private and public life that artists usually took from the world that surrounded them. Everyday themes in art go at least as far back as Ancient Greece. Scenes of everyday life of common people with their daily rituals were depicted on amphorae or murals, moved into miniatures or stained glass windows with religious scenes. Finally, in the seventeenth century, they became central themes of artistic depiction. Foremost here is Dutch art, particularly Johannes Vermeer with his chamber scenes from urban life.

Johannes Vermeer. Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window. 1657—1659

Photography, the new technology of producing images, gained popularity in the mid-nineteenth century and took the themes of the everyday to a new level. The creation of the Kodak photographic camera ushered in the era of the mass snapshot, which eventually made anything and everything the object of photography. The democratic nature of this new art form led some to praise, and others to criticize it. Be that as it may, it helped us see more details of everyday life.

A new strain in 1970's documentary photography can be described in the words of the American photographer Stephen Shore, to whose work themes of the everyday were central: “I wanted to take a picture that felt natural, that felt like seeing and didn’t feel like picture-making.” Although Shore's photographs still looked highly professional (with an eye to composition and structuring the frame), time dictated changes in our understanding of photography. Thus, the parallel concept of 'the snapshot' arose, with its aesthetics of amateur photography, and was picked up by wide swathes of art photographers, such as another American photographer Nan Goldin. European and American photographers were not constrained in their choice of protagonist or scene — every new thing that appeared in society was thoroughly documented by curious authors: whether people of non-standard appearance (works by Diana Arbus), New York bohemians propagating the sexual revolution, drug addicts or people with AIDS (works by Nan Goldin), the nightlife (works by Ed van der Elsken), marginalized communities (works by Anders Petersen), etc.

At the same time, the scope of themes showing through the lens of Ukrainian photographers of the time was closing in ever tighter. The laws in Ukraine, then part of the Soviet Union, forbade unsanctioned photography not only of 'strategic objects' (such as railways, factories, military facilities) but even street photography. The nude was a separate taboo.

The powers that be even dictated aesthetics: photography was to contain no extravagant experiments — these were branded 'formalism,' and led to outright persecution of their authors. Proper Soviet photography was to be 'correct,' staged, carefully selected. Essentially, it was propaganda — photography of this kind was meant to show a strictly positive view of Soviet life, stress the advantages of a Socialist utopia. Documentary photography that would reveal other sides, a variety that was not always attractive, was prohibited. And so, until the slight liberalization of social life in the so-called Khrushchev Thaw of the 1960s, Ukrainian photography shows no examples of direct documentary photography along the lines of European or American photography (at least, if such examples exist, they have not yet been found or studied). Audacious experiments begin in the late 1960s in a circle of Kharkiv photographers, now known as the Kharkiv School of Photography.

The Kharkiv School of Photography is an umbrella term for several photographic groups and lone authors — three generations of photographers in all, who shot from the late 1960s in Kharkiv. The term encompasses about two dozen names, including Evgeniy Pavlov, Juri Rupin, Boris Mikhailov, Oleg Malyovany, Oleksandr Suprun, Anatoliy Makiyenko, Oleksandr Sitnichenko, Gennadiy Tubalev, Viktor and Serhiy Kochetov, Sergey Bratkov, Sergei Solonsky, Misha Pedan, Valerii and Natalia Cherkashyn, Igor Manko, Volodymyr Starko, Roman Pyatkovka, Igor Chursіn, Andrey Avdeyenko; and four groups: Vremya ('Time'), Gosprom, The Group of Immediate Reaction and Shilo ('Awl'). They not only created documentary photography to tell of all aspects of life in the Soviet Union, but incorporated artistic elements to interpret, exaggerate, distort, and thus create even more apt images of the era.

Artists of the Kharkiv School of Photography created many works that documented and interpreted the Soviet and post-Soviet everyday. We can get a broad sense of the themes, methods, and formats of their work by browsing through the online archive “Kharkiv School of Photography: Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics,” created as part of the Ukraine Everywhere program of the Ukrainian Institute.

The unattractive Soviet everyday made its first appearance in the works of Ukrainian photographer Boris Mikhailov (this now internationally known artist has lived in Berlin in recent decades). His photography — as well as that of his Kharkiv colleagues — was a complete opposite to the official, propaganda photography cultivated in the Soviet Union. Whereas mainstream photography aimed to produce pathos-filled valorization of the Soviet citizen and their working days, artists in undeclared opposition to it clearly wanted to show another side — the everyday and the intimate, that which was painstakingly hidden by the Soviet authorities. To them, photography “served the chief cause — to de-heroize the Soviet,” as Mikhailov put it in an interview while describing his artistic approach.

The theme of the everyday was widely explored in his Unfinished Dissertation project — a photo book with black and white photography and handwritten texts, which he created in 1984—1985. At first glance, the book may appear as a bit of a hodge-podge collection of amateur snapshots. However, this simplicity hides an unsentimental and frank look at the mood in Kharkiv, and people's lives in the final decade of Soviet power. The juxtaposition of photographs (the visual) with texts (the verbal) is somewhat out of character: the handwritten sentences are unexpected thoughts or excerpts from recently read books and have nothing to do with the images. Generally, Mikhailov pays a lot of attention to the city and its changes through history; these themes can be traced in all of his photographic series. With his maverick vision, Mikhailov was a leading figure for many of his friends from the Vremya group, as well as subsequent generations of photographers. His works today are widely known and analyzed, which is why we propose to look at the works of those authors who are as yet less well known.

Viktor and Serhii Kochetov are a father and son who only position their works as joint projects. Never part of any artistic group, they have always kept somewhat to themselves. However, interactions with Boris Mikhailov moved Viktor Kochetov, who worked as a reporter for Soviet media (and thus part of the official photographic establishment), to shoot 'for himself.' This meant creating the sort of photography that would not have been accepted by any editor of any paper at the time. The camera eye caught everything — the camera was a diary of sorts. Their photographs represent their daily routes, the way to work and back home, as well as their strolls. Even in shooting central streets, they selected in favor of 'behind-the-facades,' which was usually ignored by professional photographers and reporters — rather than frontal, facade, views. Their landscapes are marked by a focus on peripheral and marginalized places.

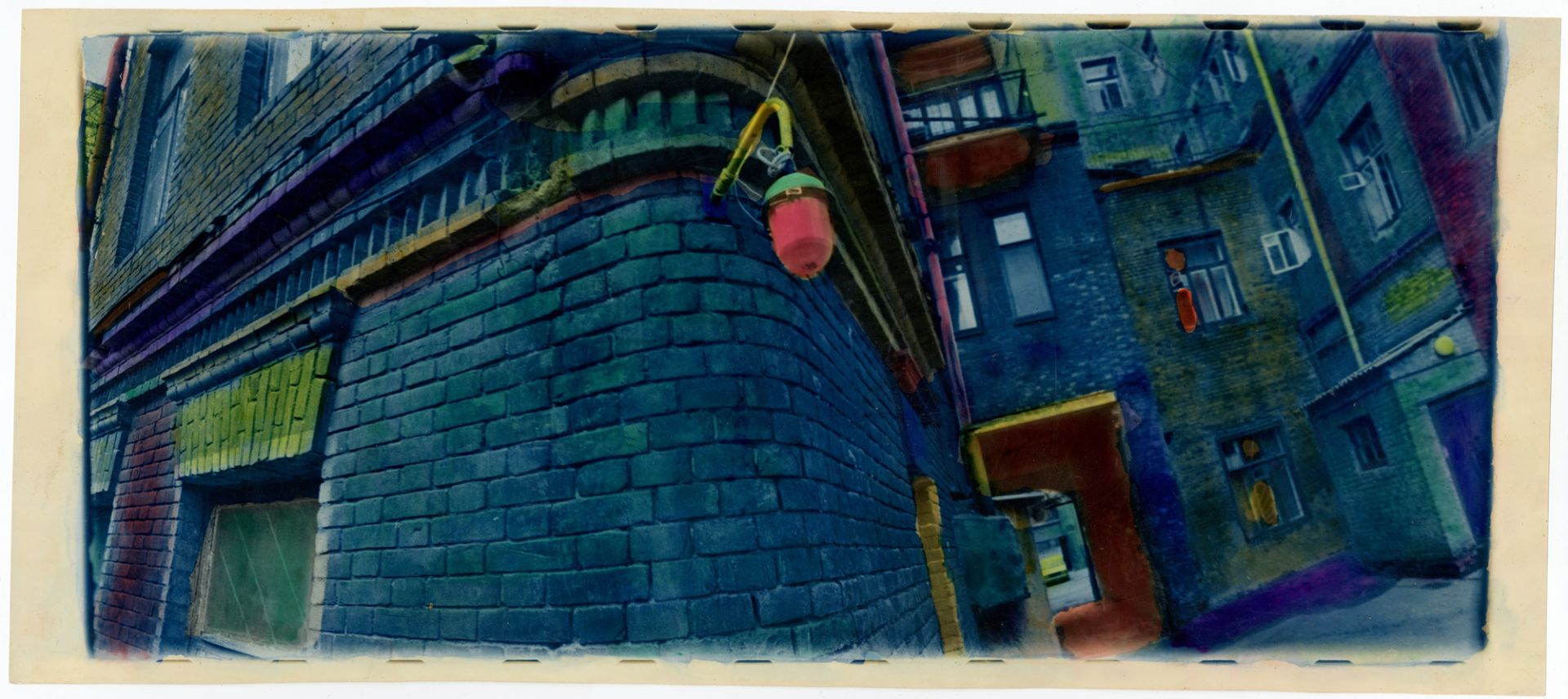

© Viktor Kochetov, Serhii Kochetov. Petrovskoho St., 1995. MOKSOP collection

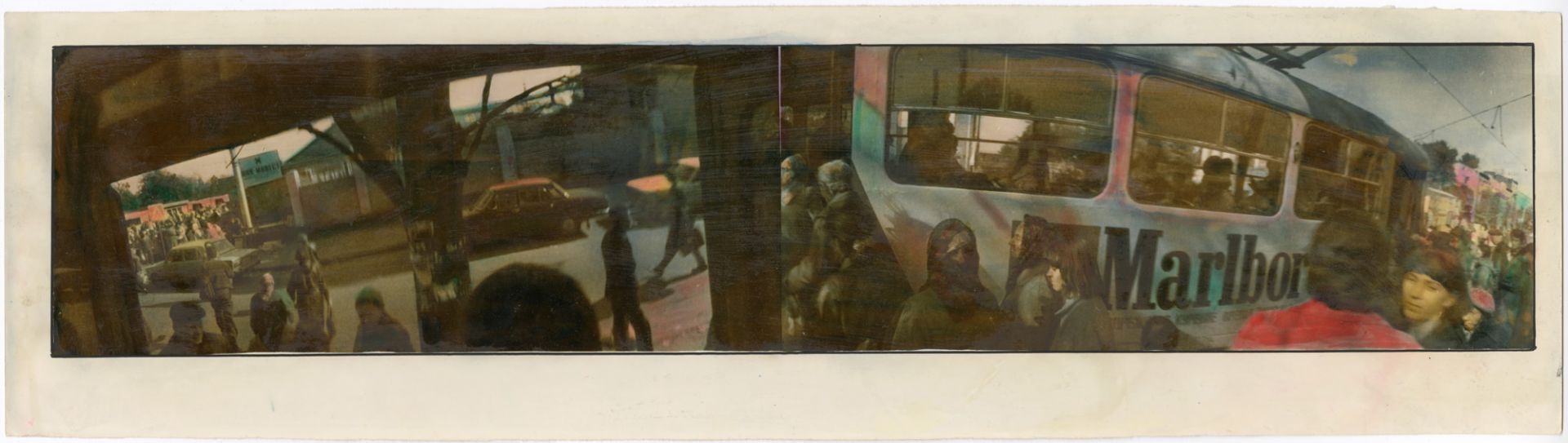

In the Kochetovs' photography, the everyday reveals itself as a dichotomy: in one photograph we see an old Soviet “Festival” radio transmitter, but the snapshot itself is dated 1994 — i.e., after the collapse of the Soviet Union; in another, we see “Marlboro” inscribed on shopping bags and trams. But such was the reality in 1990's Ukraine — everything was mixed, with no correspondence to place or time.

© Viktor Kochetov. Summer Tram, 1995. MOKSOP collection

A characteristic move of the Kharkiv school of photography is the technique of coloring the prints. But whereas other representatives of the Kharkiv school tried all manner of techniques — the collage, overlaying of slides, solarizing, toning — the Kochetovs constrained their experiments to just one. The bright-colored, striking, weird painting (such as blue faces or a pink sky, for instance) serves the authors' intention to bring forth a strong sense of dissonance in the viewer.

© Viktor Kochetov, Serhii Kochetov. What are those? Those are garages, 1995. MOKSOP collection

Some photographs by the Kochetovs can be viewed through a historical lens: they had a strong interest in old cars. Many photographs show Soviet Moskvitches, Chaikas, and Pobedas in various conditions. It is very striking to see these symbols of time documented at close quarters, like majestic monuments.

© Viktor Kochetov, Serhii Kochetov. Kharkiv. Saltivka. Moskvitch, 1997. MOKSOP collection

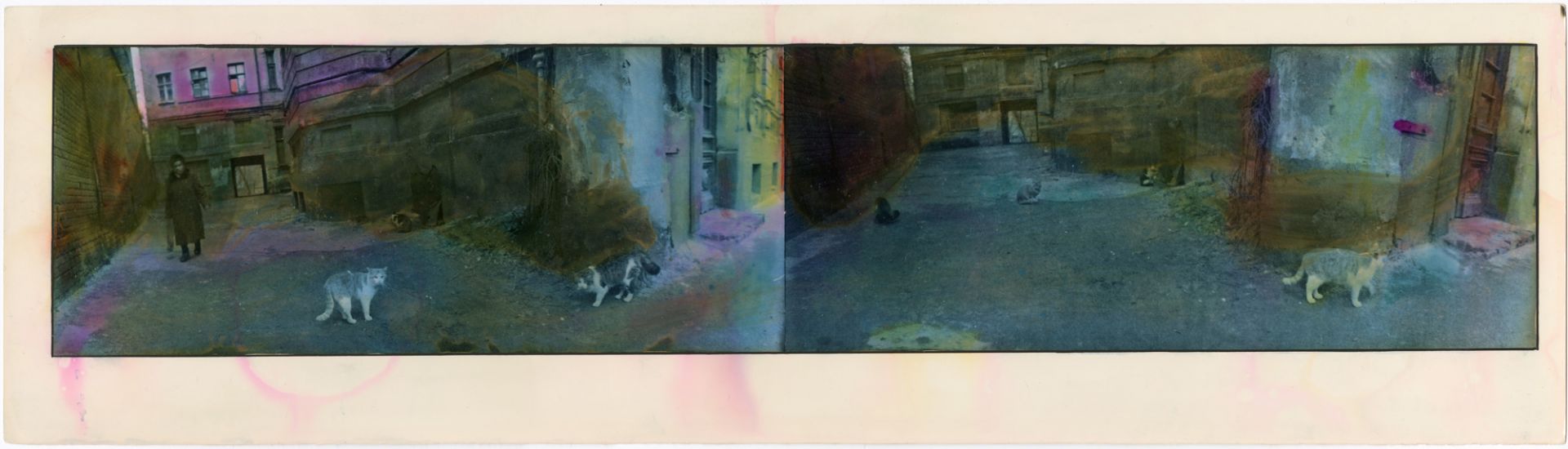

Boris Mikhailov has a series entitled Case History, in which he photographed homeless people, and thus documented a new social stratum that arose in Ukraine only after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The Kochetovs did not photograph homeless people, but their landscape works from the 1990s contain many street dogs and cats. They are a characteristic trait of post-Soviet public space, where, uncared for, street animals began coming together into packs to survive.

© Viktor Kochetov, Serhii Kochetov. Street Cats, 1995. MOKSOP collection

In Kochetovs' works, the mundane turns surreal. Perhaps it was the boredom and apathy of life in Soviet and post-Soviet reality that motivated this turn. The Kochetovs use photography as an ironic way to depict the absurdity of (post-)Socialist existence.

© Viktor Kochetov, Serhii Kochetov. Station. Construction Site, 1982. MOKSOP collection

Other authors of the so-called first generation of the Kharkiv school of photography were more interested in themes of the nude body and sexuality.

The next, second generation, much like the aforementioned authors, paid much attention to the everyday, to the changes in surrounding space and people. Prominent here was a group formed by Igor Manko and Guennadi Maslov in 1985, first titled Kontakt, and later Gosprom. The group also included Volodymyr Starko, Boris Redko, Misha Pedan, Leonid Pesin, Kostiantyn Melnyk; Sergey Bratkov later joined instead of Maslov. The young photographers interacted with the Vremya group, and showed them their photographs, but diverged from them in 'the blow theory' [a concept formulated by Kharkiv photographers, whereby arresting, sometimes aggressive photographs are meant to “strike” the viewer, immediately grabbing their attention and thus forming a strong impression — ed.] As Igor Manko noted in an interview, their group “primarily strove for documentary reliability, a return to realism, showing true aspects of Soviet reality in its decay.” They were interested in the unadorned Soviet everyday.

© Misha Pedan. Untitled (from the series The End of La Belle Époque), 1986. MOKSOP collection

© Misha Pedan. Untitled (from the series The End of La Belle Époque), 1987. MOKSOP collection

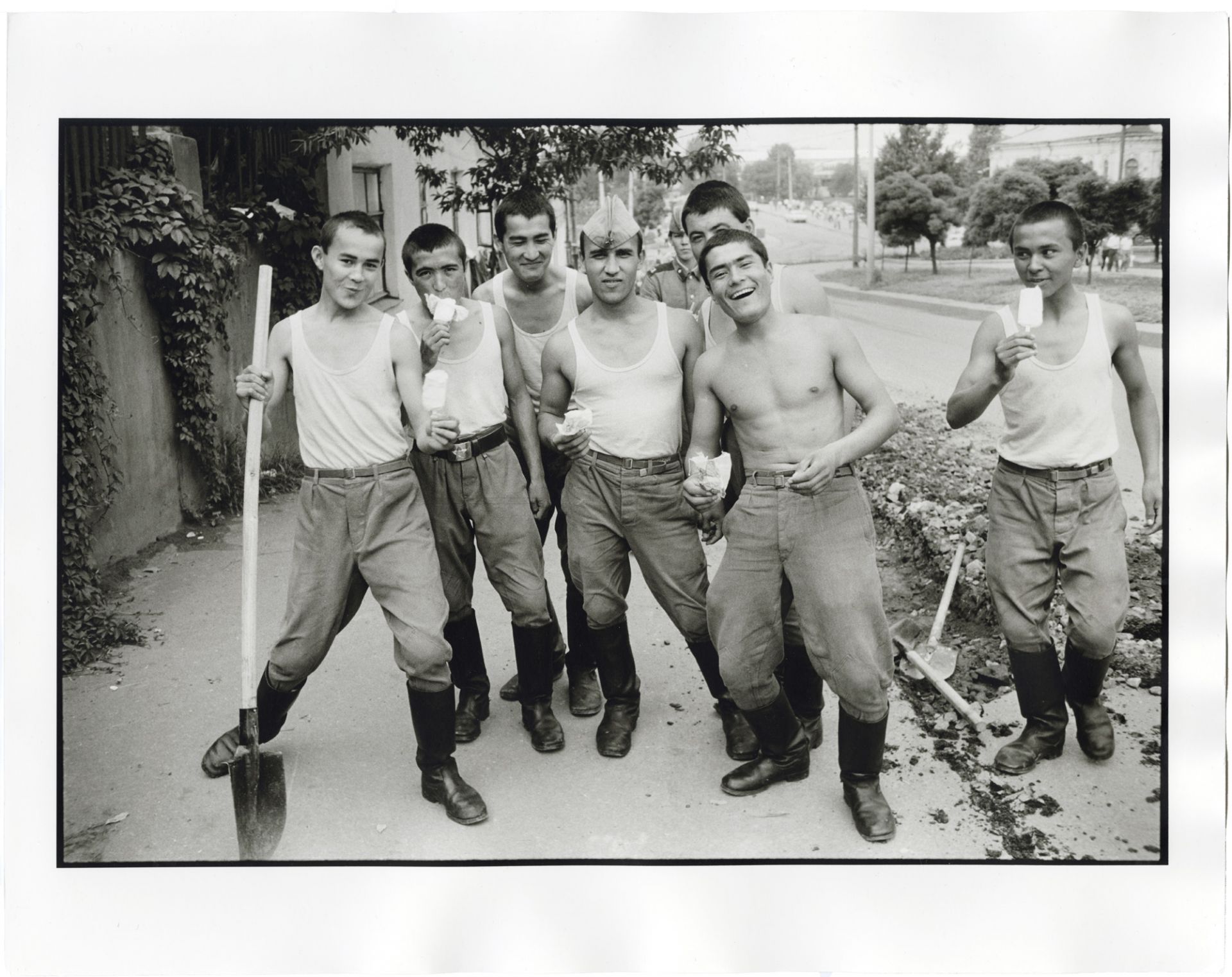

Misha Pedan, who emigrated to Sweden in 1990, provided almost all-encompassing documentation of the final years of the Soviet Union. His photographs from 1986—1990 depict various street scenes, where people often look into the camera or strike ironic poses. In his works, the everyday shows in the clothing of the subjects of his photographs, their facial expressions, and their poses. By the late 1980s, young people behaved more freely, they were no longer afraid of the camera, they strike brave, perhaps even slightly defiant, 'cool', and 'modern' poses. The poses and faces of older people still sometimes show reserve or shyness, but again, there is no fear of being photographed. This is a telling mark of the changes in social moods, of how people were becoming freer and less uptight. This sense of sudden freedom was in the air, and Misha Pedan managed to document it. The photobook The End of La Belle Époque, which is comprised of his 1980s photographs, was published not that long ago, in 2012. In one interview, Pedan describes the album thus: “This freedom, this initial stage of freedom, was beautiful. This book serves a double purpose: on the one hand, it depicts the Soviet exotic, but at the same time it shows ordinary life.”

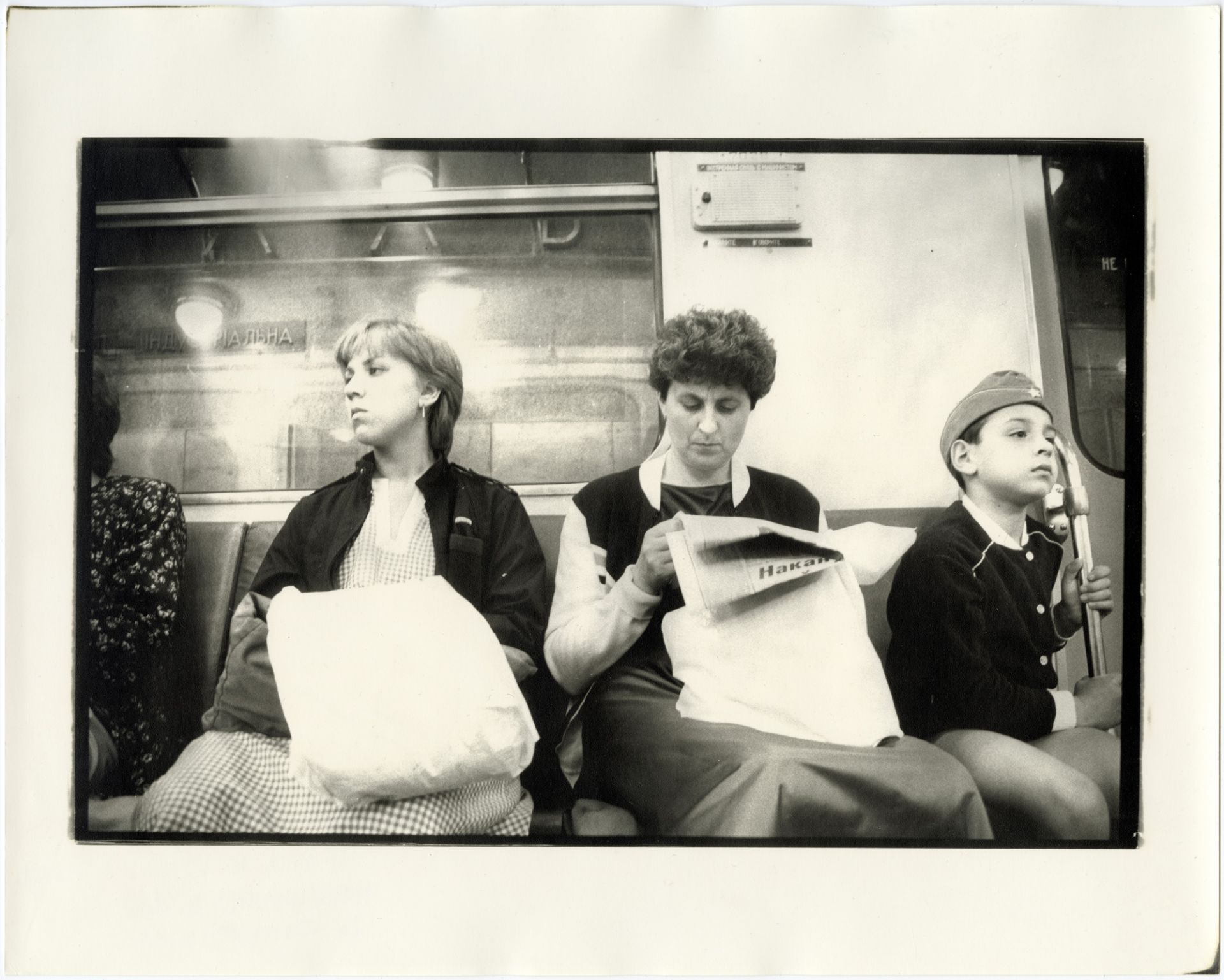

© Misha Pedan. Untitled (from the series M — Metro), 1986. MOKSOP collection

© Misha Pedan. Untitled (from the series M — Metro), 1986. MOKSOP collection

Ordinary life is also shown in Pedan's penultimate photo album, entitled M, and dedicated to the Soviet subway. In 1985—1986 Misha Pedan took candid photographs of subway passengers in their, and his, daily 45-minute work commute every morning and evening (it was still prohibited to openly photograph daily life). The 80 black-and-white photographs only show sad and mistrustful faces: it seems as though there were no happy people in the Soviet Union at all. In preparing the book for publication, the publishers took pains to find old Soviet photographic paper, in order to create an appropriate impression: “The photographs look dirty and dark — precisely the effect I was going for.” The photographs, the text, and the book's overall visual design come together to give a striking image of the average Soviet person.

Other members of the Gosprom group were also interested in manifestations of the everyday, and found an appropriate aesthetic to convey them: “If I tried to sum up the aesthetics of the Gosprom group in a word, the word would be 'Indifference'”, Pedan said in an interview. And, indeed, the photographs can be said to be boring and grey, but that is precisely the aesthetic that gets at the final years of the Soviet Union when viewed without irony or sarcasm, as was the preference of the first generation of the Kharkiv school. Igor Manko, a co-founder of the Gosprom group and curator of the “Kharkiv School of Photography: Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics” project describes the artistic attempts of his colleagues thus: “Within this general line [of documentary precision — ed.] Pesin and Starko tended towards the critical anti-Soviet expression, while Borys Redko preferred the ironic demonstration of the absurdity of the surrounding life.”

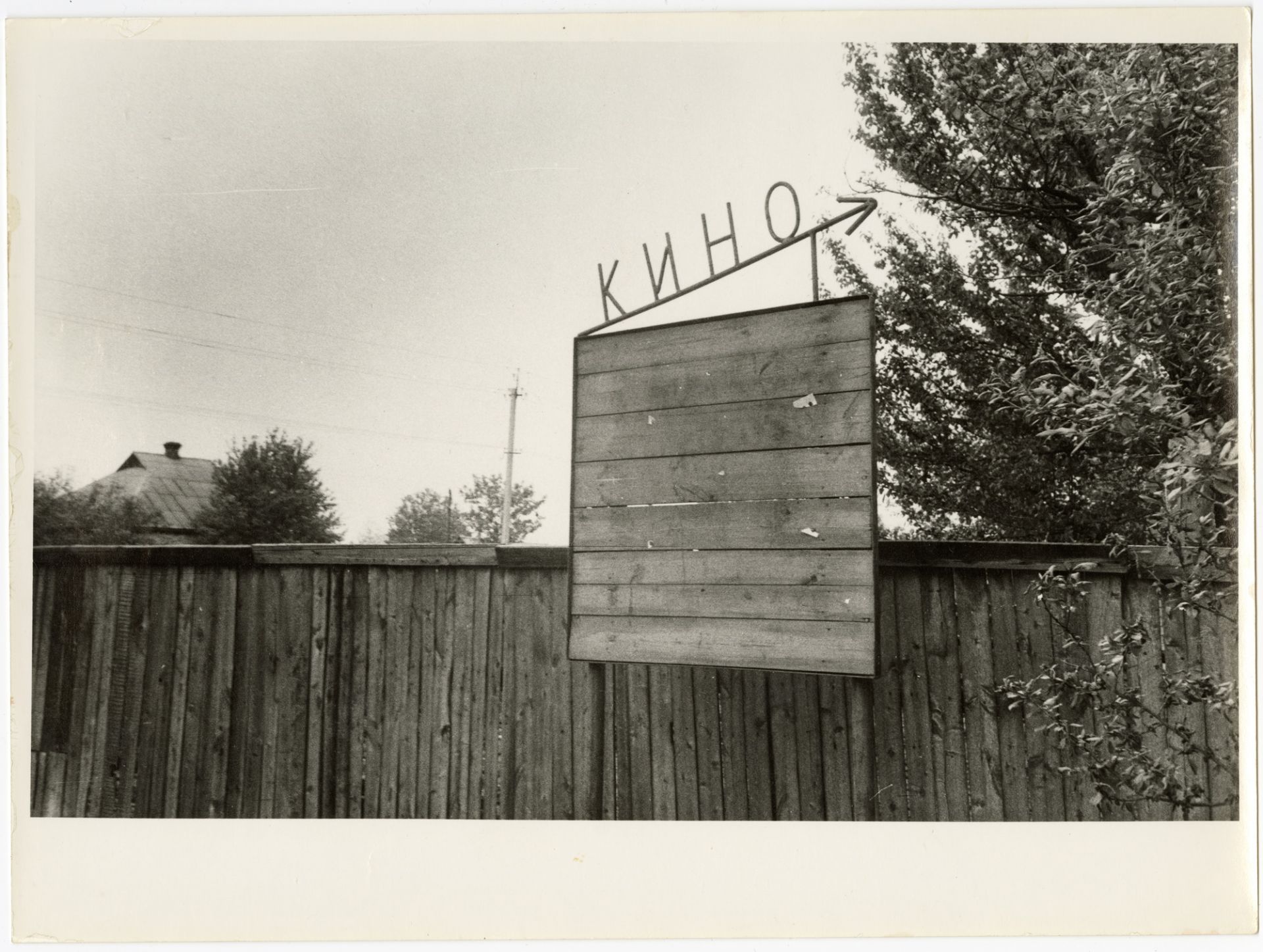

© Volodymyr Starko. Untitled, 1984. MOKSOP collection

© Volodymyr Starko. Untitled, 1980. MOKSOP collection

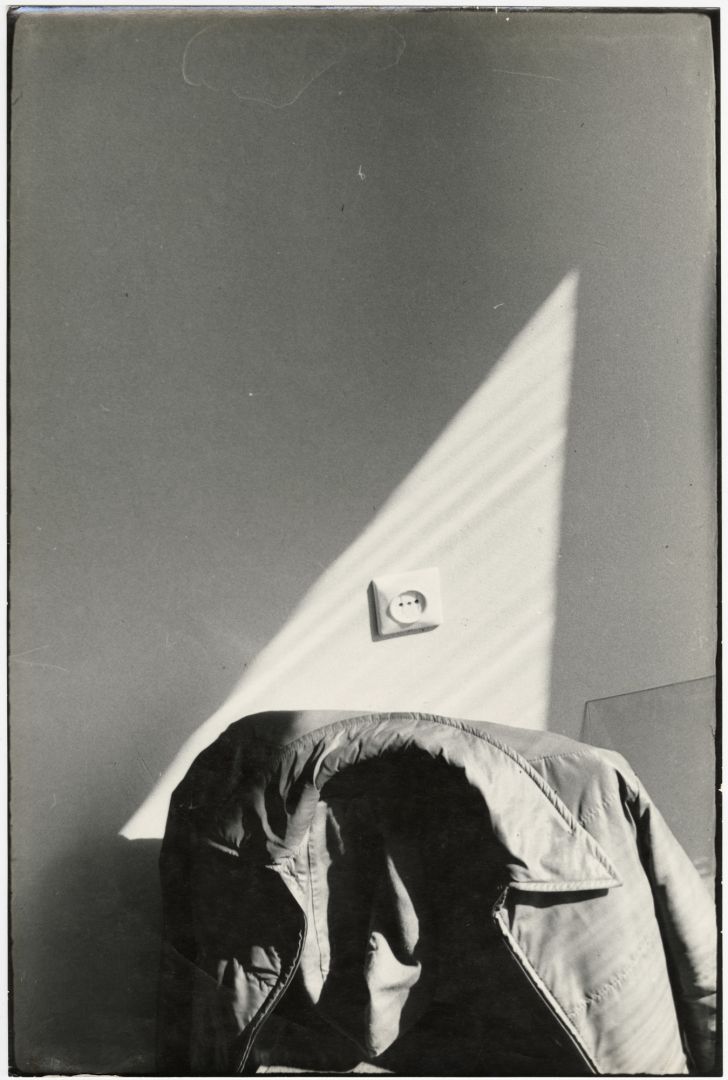

Volodymyr Starko's photographs present a direct and somewhat detached look at dilapidated public space: here a pile of broken asphalt, there an empty notice board of a cinema, elsewhere twisted wires of unclear purpose in the middle of a courtyard. In most of his works, space appears abandoned by humanity. The photograph of the empty chair with a jacket draped over its back is also symbolic: it's as if the owner of the piece of clothing is no longer with us, their place stands vacant. Or vice versa, we see a crowd preoccupied with their own affairs while waiting for transportation — the daily automatic ritual of the work commute.

© Volodymyr Starko. Untitled, 1982. MOKSOP collection

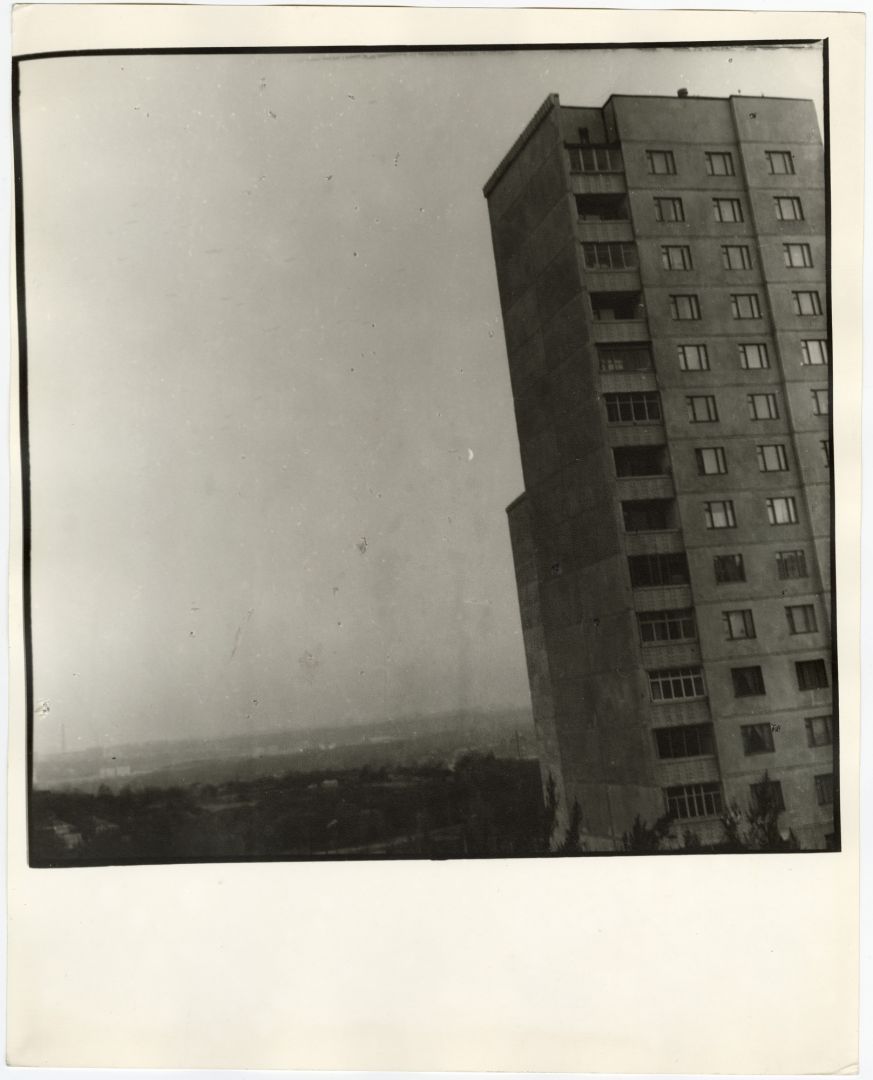

Striking in Boris Redko's works is the repeating narrative of prefab panel highrise buildings and projects. Construction of these in the Soviet Union began in the 1960s, and by the 1980s they dominated the city outskirts. In Boris Redko's photographs, they aren't direct objects of photography; rather they accompany the author's attempts to photograph his childhood courtyard, a view from a window, or even a landscape with the moon or baby carriages. These photographs evoke the feeling of a gray 'urban jungle,' where people are almost absent, squeezed into one of many boxes not meant to differ in any way from other, neighboring boxes.

© Boris Redko. The Moon, 1983. MOKSOP collection

© Boris Redko. Untitled, 1988. MOKSOP collection

© Boris Reko. Saltivka. Football, 1983. MOKSOP collection

The theme of the unadorned everyday seems to form a closed cycle in the works of the Shilo (“awl”) group, the so-called third generation of the Kharkiv school. The group was formed in 2010 by photographers Serhii Lebedynsky, Vladyslav Krasnoshchok, and Vadym Trykoz, who eventually split away. Like their predecessors, these photographers frequently resort to irony, and see it as their function to 'prick' (hence 'awl') the somewhat sleepy photographic milieu as it existed in Kharkiv in the 2010s. They created a photo album entitled The Finished Dissertation as an homage to Boris Mikhailov, both an attempt to build bridges between the generations, and also to scoff at a recognized master. They used the same aesthetic Mikhailov resorted to in his Unfinished Dissertation, the same gray, boring photography combined with ironic texts to now document modern Kharkiv. However, it is hard to tell the difference, as if time in this place had stopped still.

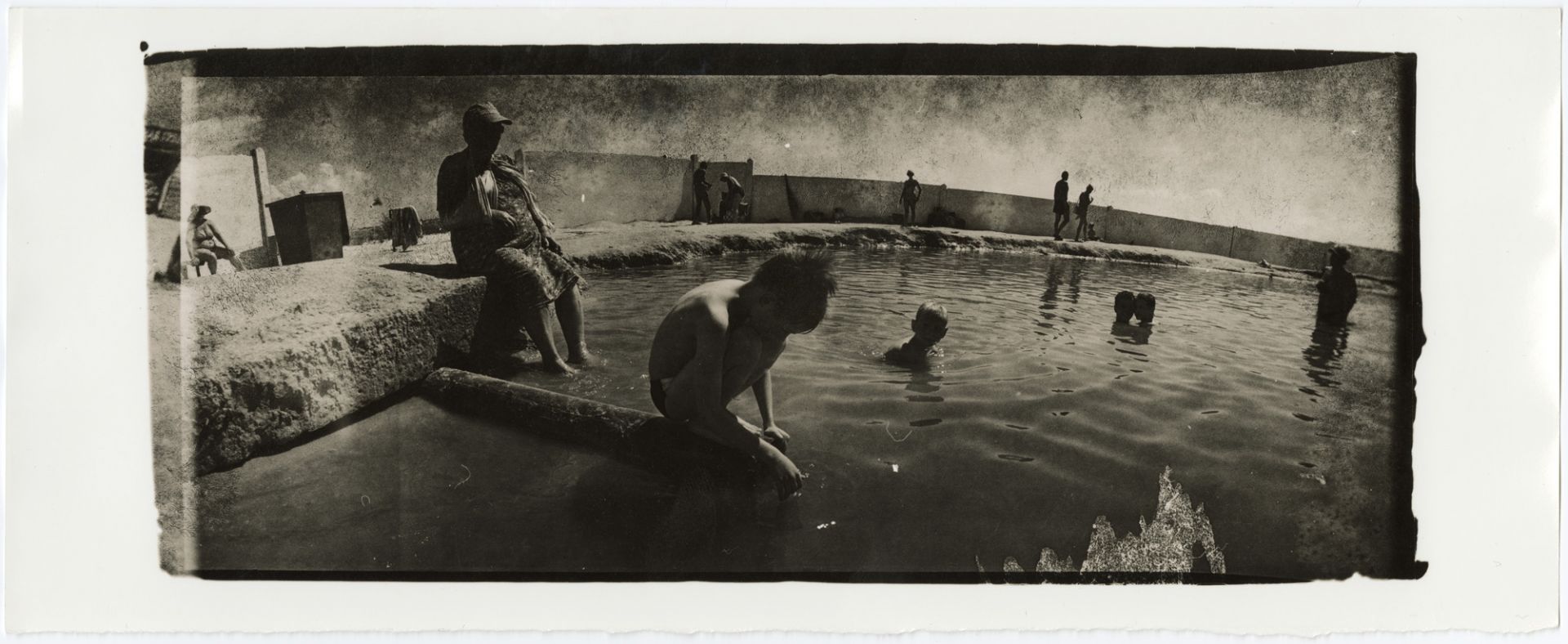

© Serhii Lebedynskyi. Untitled (from the Arabat Spit series), 2011. MOKSOP collection

To sum up, representatives of the Kharkiv school of photography were drawn to the minutiae of life. The majority of their oeuvre is sort of a game with these insignificant details. In a situation where the abovementioned works could not be exhibited, or where their very presence in an exhibition led to their removal and the exhibition's closing, it's as though authors took these photographs only for their own private use, were free to play with them as they pleased, with no constraints of technique or aesthetic point. Anything is possible in play. This is why Kharkiv photography, with the centrality of irony in many of the series represented here, is entirely consistent with Postmodernism. Irony and play manifested in the way of looking at things. They were a way of fighting Soviet boredom and the grayness of the mundane. As Misha Pedan noted in one of his interviews: “If there was any unifying theme to the Kharkiv school, it was the sense of the absurdity of the surrounding world, and an ironic attitude to it. This irony allowed us to continue living while knowing that the world is absurd.”

This essay was written for the project “Kharkiv School of Photography: Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics,” which is being implemented as part of the Ukraine Everywhere program of the Ukrainian Institute

Alina Sanduliak is a historian of photography, independent author, and curator. Her research interests include contemporary world photography, methods of creating photographic projects, as well as classical Ukrainian photography. Her articles have been published in different online magazines such as Bird in Flight, Art Ukraine, Korydor.