Kateryna Iakovlenko. Art after #Metoo: Image and (Un)Acceptable Provocation in Modern Ukrainian Visual Culture

Published in English in BlockMagazine (Poland), in Ukrainian — on LB.ua Livy Bereg platform (Ukraine)

After the high-profile global movement #Metoo, which in Ukraine developed a broader framework #яНеБоюсьСказати (“IAmNotAfraidToSpeakOut”, an information campaign against violence against women in Facebook in Ukraine), the cultural world began revising fixed standards, laws, and communication frameworks. This text will discuss the boundaries of feminist criticism and acceptable provocation in Ukrainian art using the works by Sergey Bratkov as an example.

Sergey Bratkov (b. 1960, Kharkiv) is a world-renowned artist, a participant in the Venice Biennale (2005, 2007), Sao Paulo (2002), and the Manifesto (2004). In the 1980s he was a member (together with Misha Pedan, Boris Redko, Volodymyr Starko, Igor Manko, Leonid Pesin, Konstantin Melnik) of the Kharkiv art group Gosprom, and in the early 1990s, he co-founded the Group of Immediate Reaction (together with Boris Mikhailov and Sergiy Solonsky, with the participation of Vita Mikhailov). His creativity is often provocative, and his work has always received mixed reactions, accusations of sexism and pedophilia, or other criticism, including protests, from some in the feminist community. Thus, his work Khortytsia (2009) was sent for review to the Commission on Morality in Ukraine in 2010, when it was examined during transportation across the Russian-Ukrainian border. In the same year, activists from FEMEN (a women's activist group that conducted outrageous and provocative acts on political topics; with a characteristic feature in their appearance — the activists were almost naked, wearing a traditional Ukrainian headdress — a flower wreath. — Ed.) intervened in the PinchukArtCentre contemporary art center in Kyiv, where that same work Khortytsia was exhibited.

© Sergey Bratkov. Khortytsia, 2009. Photo from the exhibition "Ukraine" at the PinchukArtCentre. Courtesy of the artist.

A girl in a Ukrainian national dress, lying on her back with her legs apart and her pubis open, seems to be showing her submission. The photo was taken by the artist on the island of Khortytsia (cultural and national symbol of Ukraine) on the Dnieper river and is a criticism of the stereotypical representation of Ukraine as a sex tourism destination. Bratkov was making a point that Ukrainian culture was represented in the international arena exclusively through ethnographic or sexual patterns, and opposed to the cultural lumpenization of society. Consequently, his work is a political criticism of the state's cultural policy after the 1990s. Critic and film director Oleksiy Radynsky wrote: "This photo, taken in 2009, has absorbed the key contradictions of the present times, preoccupied with an unhealthy persecution of shameful representations, but unable to cope with its own obscene core."1

Having arrived at the art center, FEMEN activists undressed to their underwear, and wearing Ukrainian national headdresses and sunglasses, holding posters "Ukraine is not a vagina!" and "Vaginart" did a photoshoot on the floor near Bratkov’s Khortytsya. In one of the photos, they also spread their legs, choosing quite provocative poses. "We do not like to be insulted. And this picture, and the exhibition as a whole, is offensive to Ukrainian women and Ukraine!” the FEMEN activist and curator of the program "Ukraine is not a brothel!" Oleksandra Shevchenko is quoted by a Ukrainian magazine Focus. Criticizing Bratkov for excessive exoticizing, sexualizing, and objectifying women and the country, the activists themselves choose the same tools: looseness, excessive sensuality, naked body, and ethnographic motifs. It looks like the woman from Bratkov's photo stepped outside the art object and is protesting against herself. So what's wrong with Bratkov's works? Why does FEMEN activism, built on its own objectification, have the right to be, but the same kind of work by a male artist is offensive and unacceptable?

In Kharkiv's late Soviet photography much attention is accorded to the female body. And this is more a story about the body, not about the woman as such, or her personality or interests. Only in a few photos of different authors do we see a person, rather than a body constitution. Most researchers who have studied Kharkiv photography insist on the close connection between the representation of the body and the political and social issues: indeed, it was a time when changes were not yet noticeable, but a desire for change was already in the air. It is unlikely that the artists perceived their work as an illustration of Foucault's ideas on biopolitics, but intuitively they chose the body to represent certain ideas.

For Bratkov, the body is a key element, too. However, he does not only exploit other people's bodies, he himself actively uses his body to create works of art. Using performance and actionism methods, together with other members of the Group of Immediate Reaction he created provocative and ambiguous political works in the early 1990s. Later, his individual works are also based on bodily experience (we are mostly speaking about his joint videos with his older brother).

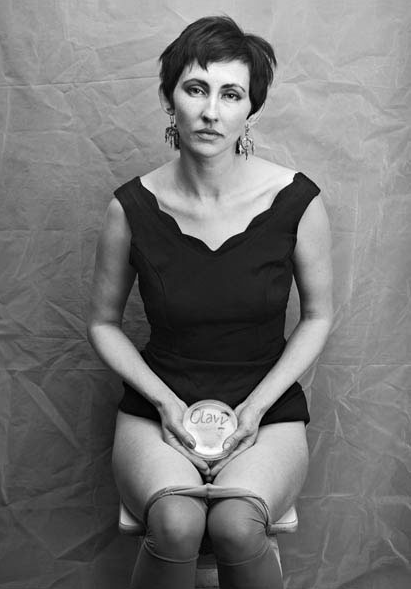

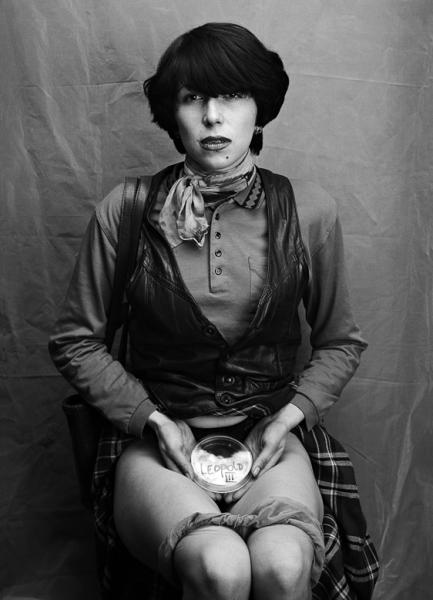

As in collective practices, in individual work, the artist unequivocally takes the side of minorities — the homeless, the children, those defeated in war, the miners, and the women as well. He speaks about their problems on their behalf or engages them in a discussion. For example, with his work Princesses (1996), Bratkov was the first in the post-Soviet artistic community to talk about reproductive violence and exploitation of the female body and childbearing by the authorities. This is a series of portraits of women, clients of a reproductive center, who are sitting on chairs with their panties down and holding sperm samples — their future children. Bratkov said that the majority of the donors in the center were former military personnel, but that information was not shared with the female clients. "These women really wanted to have children, they dreamed of conceiving from princes, and it turned out they did from soldiers," the artist himself commented on this work. However, this work is not just about talking through exceptionally taboo topics related to women's rights. In 1996, Bratkov was living between Moscow and Kharkiv, and much of his criticism concerned both the Ukrainian and Russian milieu. It is worth remembering that in 1996 the first Chechen war had been going on for the second year, and Grozny, the capital of the Chechen Republic, had been destroyed. A country constantly at war always needs new soldiers, new people who will give their lives for the authorities. So, Bratkov's Princesses series has strong political connotations and includes criticism of violence. Could the artist have created an equally strong image using a male body, or without featuring the body at all?

© Sergey Bratkov. From Princesses, 1996. Courtesy of the artist

Unlike Bratkov, Alina Kleytman was lucky (one might say ironically) to be born a woman. After all, all her provocative images now fit into newer forms of feminism, including object-oriented feminism. Kleytman is a Kharkiv artist of a new generation and a follower of Bratkov. Common features for both artists are performativity, provocation, and corporality, which never fail to undermine established stereotypes, social, cultural, and political clichés. Kleytman’s heroine savors her beauty and excessive sexuality, but at the same time does not allow men to be too close. Playing with 'female themes', the artist spells out her painful relationships with parents, issues of beauty and aesthetics, survival, and international politics. Her woman also takes off her panties, but this time not to show the world her genitals, but to shove money or contraband there in order to transport it across the border. Kleytman is now working on new topics pertinent for Ukraine today. And Bratkov's works, unfortunately, have not lost their relevance either. The Russian Federation continues to start wars, one of which is going on in eastern Ukraine. As for the issue of women's rights — it is becoming relevant again due to the conservative turn in Europe.

© Alina Kleitman. The Border, Video. 1'28'', 2017. Courtesy of the artist

When reviewing established canons with criticism of violence, we need only to remember what means of communication we use to do it. Are we replacing one kind of violence with another? Today's art is surprisingly agenda-driven, both socially and politically. The framework of established norms and prohibitions is very fragile. Art is often questioned and subjected to censorship. At the same time, the language of the artistic imagery is a strong argument in the struggle against hatred and social injustice. And if this language is capable of changing communication, influencing political decisions in a constructive way, influencing the viewer, forcing them to think about humanistic questions, — is there a difference then whether this work was created by a male or a female artist?

The essay was written for the project "Kharkiv School of Photography: From Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics", implemented within the program Ukraine Everywhere of the Ukrainian Institute

Kateryna Iakovlenko, Research Platform at the PinchukArtCentre

Sources

- Oleksiy Radynsky. Ukraine as a vagina. Media Detector, February 10, 2010