Małgorzata Radkiewicz. Photography as a “Counter Culture” in Communist Poland and Soviet Ukraine in the 1970s and 1980s

The essay in Polish published on Fototapeta

In the Eastern Bloc of the 1970s and 1980s, artistic expression was frequently an act of resistance against oppressive reality, against its grayness and hopelessness. In order to identify and compare techniques and stylistic devices used by photographers of that era, we could juxtapose the work of Polish visual artists grouped in the Lodz collective Filmowy Warsztat Filmowy [Cinematic Form Workshop] and that of photographers from Kharkiv in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic who comprised the Vremia group. This juxtaposition is geared not towards a universalizing interpretation that would negate differences arising from the particular circumstances of each country or its social and political situation, but rather towards pointing out similarities between the artists’ attitudes and their formal approach. The early 1970s were a time of increased activity of artists and photographers who were trying to create a type of visual 'culture of resistance,' in opposition to the imagery and vision of reality imposed by the official ideology. It was this resistance and searching for alternatives that led to the emergence of the Eastern Bloc’s 'samizdat' tradition — the unofficial, underground circulation of literature and art, critical of the system and the regime. Illegal, uncensored works, as well as their duplication and dissemination, offered not only alternative content but also alternative forms — often mandated by material limitations. Lack of paper and good paint dictated a particular type of printing technique and graphics, as well as a format most often associated with fliers and zines.

Artistic photography of the 1970s and 1980s references the samizdat strategy of creativeness and overcoming limitations (censorship) and insufficient resources (paper, printing techniques), expanding the creative process to include manipulation of the materials themselves. However, for this to even take place, there needed to be an atmosphere of mutual support in oppositionist thinking and formal experimentation. It might be said that one of the driving forces bringing artists together was precisely the desire to function in their own environment, among like-minded people. In groups that more often than not consisted of friends, it was easier to try different avenues — eg., visual arts, performance — of tackling reality and the ideologization of art and media. Members of these groups initially didn’t necessarily intend to create a cohesive current in art, a recognizable formation, or a school, but rather to form a group of artists that had a similar, oppositionist attitude, while at the same time looking for their own language of artistic expression.

It is in this light that we can examine two groups — one from Poland, one from Soviet Ukraine, both of which consisted of visual artists and photographers. The first of these groups is the Cinematic Form Workshop, established in Lodz in 1973 by members of the Zero-61 photographic group: Józef Robakowski, Wojciech Bruszewski, Andrzej Różycki, and Paweł Kwiek, who were later joined by Ryszard Waśko, Antoni Mikołajczyk and others. The Lodz Workshop acted as a section of a Film School research group created by students and lecturers disappointed with the school’s program and teaching methods. The name 'workshop' was meant to underscore the group’s egalitarianism, the processual nature of its actions, and its openness to experimentation and creative exploration.

The second group was created in Kharkiv in the early 1970s, and its name — Vremya (Время), which means time — signaled its aim to act in real-time, in response to current circumstances and projected visions of the present and the future. The group consisted of eight creators with very different temperaments and artistic sensibilities: Anatoliy Makiyenko, Oleg Malyovany, Boris Mikhailov, Evgeniy Pavlov, Jury Rupin, Oleksandr Sitnichenko, Oleksandr Suprun, and Gennadiy Tubalev. Their group exhibition in 1983 showed that the photographers weren’t focused on creating a uniform movement, but rather developed their own styles, which underscored individuality and a subjective perspective on the world and other people.

As was the case with the Lodz group, the Kharkiv one also wanted to accentuate the diverse ways in which its members approached visual tradition and image creation, which they didn’t want to be subject to ideology or propaganda. There’s a reason why the project of an Internet database devoted to Kharkiv photography is called Kharkiv School of Photography: Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics. Underscoring the issue of censorship and new aesthetics highlights the discontent prevalent in the Eastern Bloc in the early 1970s — a time of strikes and political tension in Poland, and of critical voices among the Soviet Union’s intellectuals who demanded policies targeted more towards the people. The communist reality urged people to adopt rebellious attitudes and look for alternatives to the imposed order that governed social, economic, but also artistic life — in terms of types of education, artistic work, developing one’s style, and the functioning of the art market itself.

That is why the members of the Cinematic Form Workshop decided to revise their views of visual arts — its forms, but also the way they are presented and interpreted. In their artistic explorations, they were inspired by traditional 1920s and 1930s avant-garde — constructivism, but also the experimental films of the duo of Polish filmmakers Stefan Themerson and Franciszеka Themerson. The workshop was supposed to facilitate experimentation with form, and artistic creativity at the intersection of fine arts, cinema, video, and photography, in opposition to the official program of the Lodz Film School. However, the alternative nature of the workshop’s endeavors does not change the fact that its members received financial and technical help from the school, without which many of their experiments would have been impossible. This balancing act between acting as part of national institutions and charting an independent artistic course is characteristic of the entire communist era, during which artists were trying to find a space for free expression within the official system or on its margins.

The biggest issue for the members of the Cinematic Form Workshop was the analysis of selected media (film, video, photography) — or more precisely, their technical and aesthetic capacities. The artists aimed to expose the illusory and transparent nature of cinema and photography, revealing its materiality, conventionality, as well as its ideological, propagandist, and commercial aspects — particularly when it came to the officially produced and distributed movies.

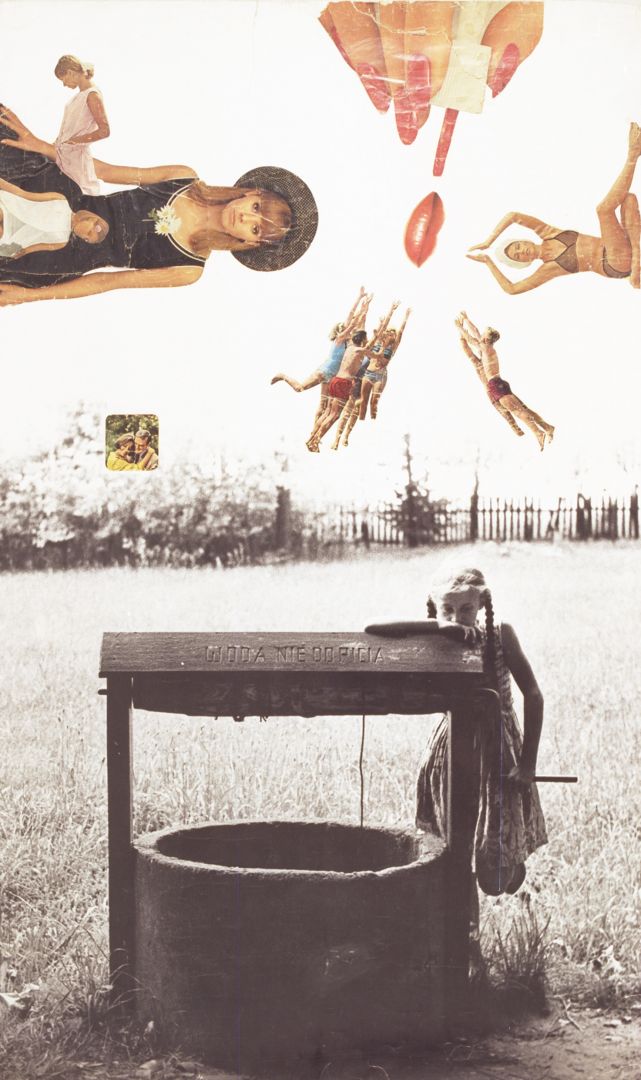

The work of the members of the Cinematic Form Workshop is characterized by self-referential reflection on visual media, its capabilities and limitations. A good example of this is the photography of Andrzej Różycki, who also references various traditions of art, particularly literature and modernist painting and its symbolism. The theme and main motif of the photograph Zatruta studnia [Poisoned Well] (1965) references a painting by Jacek Malczewski, a symbolic painter who drew inspiration from romanticism and mythology, but the collage technique used by Różycki bucks tradition, introducing figures cut out from color photographs into the black-and-white composition.

© Andrzej Różycki. Zatruta studnia [Poisoned Well], 1965. Picture from the collection of the Museum of Photography in Cracow

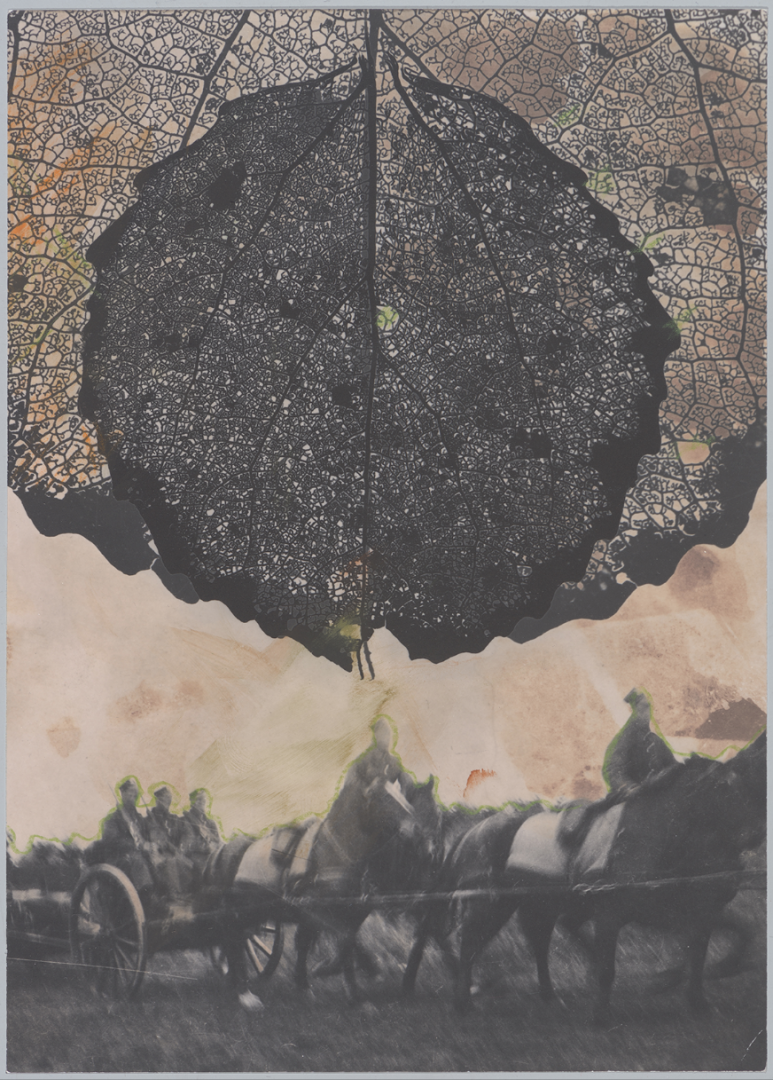

The contrast between the tonalities of the used pictures makes it impossible to draw simple comparisons between the well captured by Różycki and the multitudes of meanings of this motif in Malczewski’s allegorical visions. There is a similar poetics to the collage picture Polska jesień [Polish Autumn] (1968), which combines the motif of a colorful leaf with an archival photograph of a military procession from 1939. Such a combination of historical and natural elements shows contemporary photography’s ability to construct visual memory.

Różycki was equally inspired by cinematic tools, particularly avant-garde techniques of framing and editing images to accentuate rhythm and motion. He used them, for example, in his Projekt uruchomienia obrazu fotograficznego “Ikar” [Project of the Launching of the “Icarus” Photographic Image] (1975) which was a composition of pictures of various stages of movement arranged into a sequence that conveyed the dynamics and temporal continuity of still images. We see another type of sequence in Analiza fotografii monopolowej (Fotografia monopolowa) [Analysis of a (Monopoly Photography)]. It’s a collage of several photographs glued onto a newspaper page. The composition is time-stamped — 22 July 1982, which underscores the specific context of a national holiday during martial law. At the same time, the author has stripped the event of pathos and undercut its ideological dimension, using the word 'monopoly', which in Polish has alcoholic connotations, in the title and thus referencing how ordinary people usually celebrate the day in question.

© Andrzej Różycki. Polska jesień [Polish Autumn], 1968. Picture from the collection of the Museum of Photography in Cracow

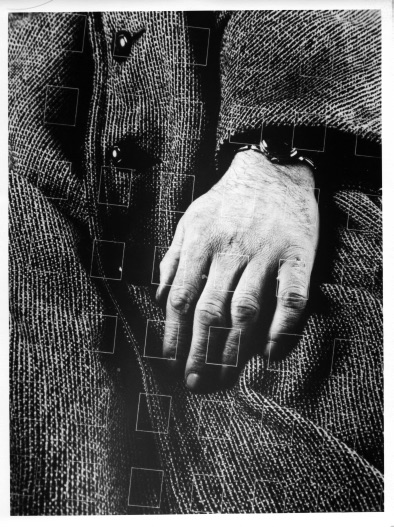

Wojciech Bruszewski’s photographs also explore framing, composition, and exposition. The title of his first exhibition, Ciąg dalszy (ręka) [Continued (Hand)] from 1971 refers to a multi-plane composition based on the concept of a 'frame within a frame', which deepens perspective, forcing the eye to look deeper into the image.

© Wojciech Bruszewski. Ręka. Ciąg dalszy [The Hand. Continued], 1970. Photo from the Arton Foundation Repository

Meanwhile, in his cycle Fotografie na płótnie [Photographs on Canvas] (1979), he used a double exposure of the photographed object in two different forms: first, he took pictures of a canvas mounted on a stretcher and then printed the pictures on photographic canvas mounted on a stretcher.

© Wojciech Bruszewski. Ręka [The Hand], 1970. Photo from the Arton Foundation Repository

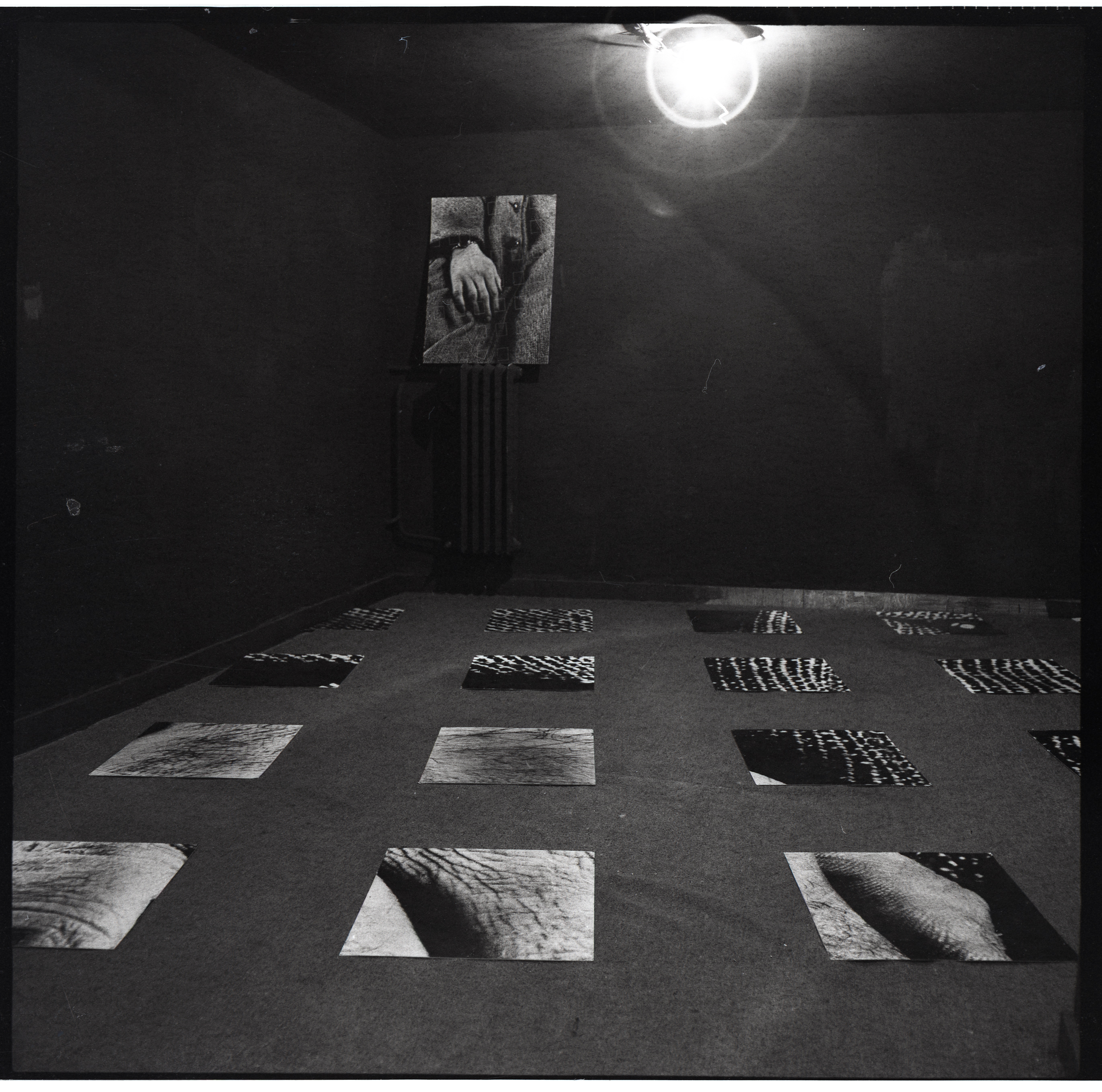

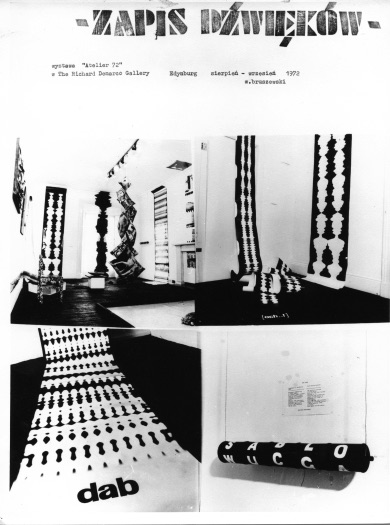

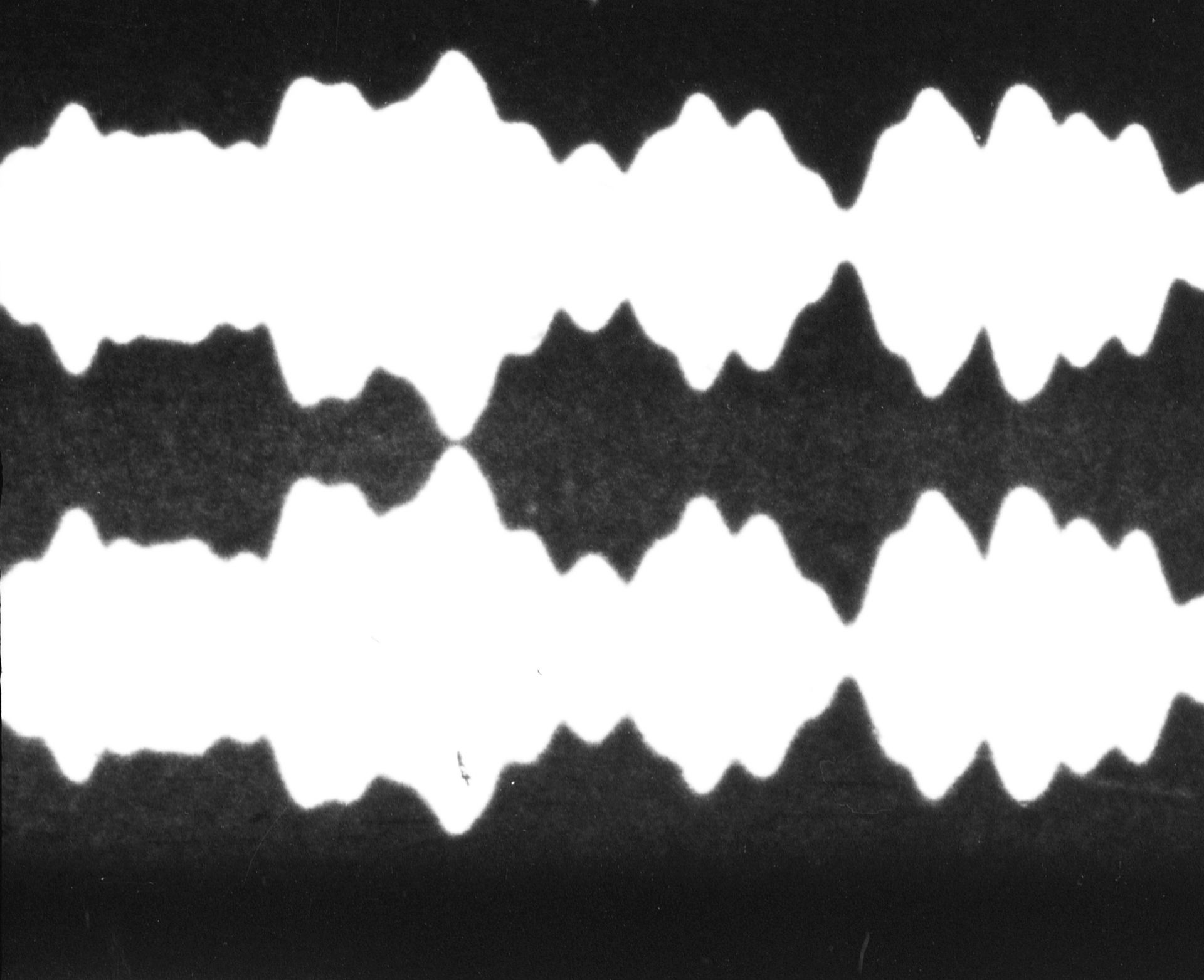

Thus, the line between photography and oil painting was blurred. The source material blended with its image, and the photographed blended with the exhibited. At the same time, the image frame was accentuated as the frame of the presented print, which laid bare the limited scope of photography, subjected as it is to a subjective point of view. The series Fotografie dźwięków [Photographs of Sounds] (presented in Edinburgh in 1972) also required its viewers to change their viewing habits. Its title suggested a combination of visual and aural stimuli. However, the exhibition was purely visual and comprised of large format images of sound waves, printed onto long stretches of paper. These unusual images, tangled on the floor like audio tapes or ECG print-outs, gave the impression that the sound was still being emitted.

© Wojciech Bruszewski. Zapis dźwięków [The record od Soumds], 1972. Photo from the Arton Foundation Repository

© Wojciech Bruszewski. Zapis dźwięków [The record od Soumds], 1972. Photo from the Arton Foundation Repository

Also for Ryszard Waśko, the Cinematic Form Workshop was an opportunity to pursue media-adjacent art. His photographs seemed intent on exploring motion and rhythm, which are typical of cinema. Photographs combined into sequences and arrangements seemed like an intermediary and inter-media work that occupied the space between traditional forms of photography and film (as well as drawings, which he often attached to his visual projects). His subsequent photographic series, dubbed collectively Portret pocięty [Fragmented Portrait], belonged to that category. The first composition from 1971 looks like a film sequence, as it is composed of groups of juxtaposed photographs that show the artist from a wide shot to a close-up of his lips. The composition directs the viewer’s attention to the relationship between the photographer and the subject, and the capabilities of the camera, whose optical functions change the nature of the picture and its significance depending on the contents of the frame and its composition.

© Ryszard Waśko. Róg [The Сorner], 1976. Photo from the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw

In 1975, the artist created Autoportret z linią [Self-Portrait with a Line] which consisted of four identical black and white portraits of a standing man struck through with two crisscrossing colored lines. On one hand, they can be read as a rejection of one’s image, on the other — they define perspective and the vanishing point of the composition. Therefore, the picture wasn’t merely a self-portrait, but also a study of photography itself and its potential for representation, similar to that which he presented in his diptych Rzeczy [Things] (1972). In it, he juxtaposed a picture of several everyday objects with the negative of the shot, which laid bare the mechanism of the photographic medium and showed the process of the creation of images of reality.

Meanwhile, his work Wstawanie [Getting Up] (1974) combines two aspects of photography: immobilization and its relationship with time — in this case, time of action. The work consists of two pictures showing the artist rising from a crouch, with the blurred second image, featuring a figure in a different position, capturing the phase of the movement. The images, which were shot some time apart, show only specific 'moments' of the action, but their juxtaposition reminds us about the temporal continuity in which the act of photography took place.

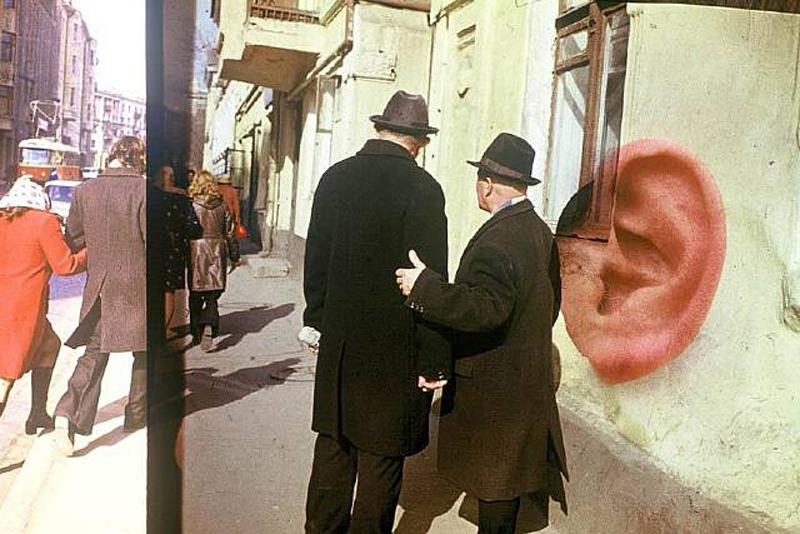

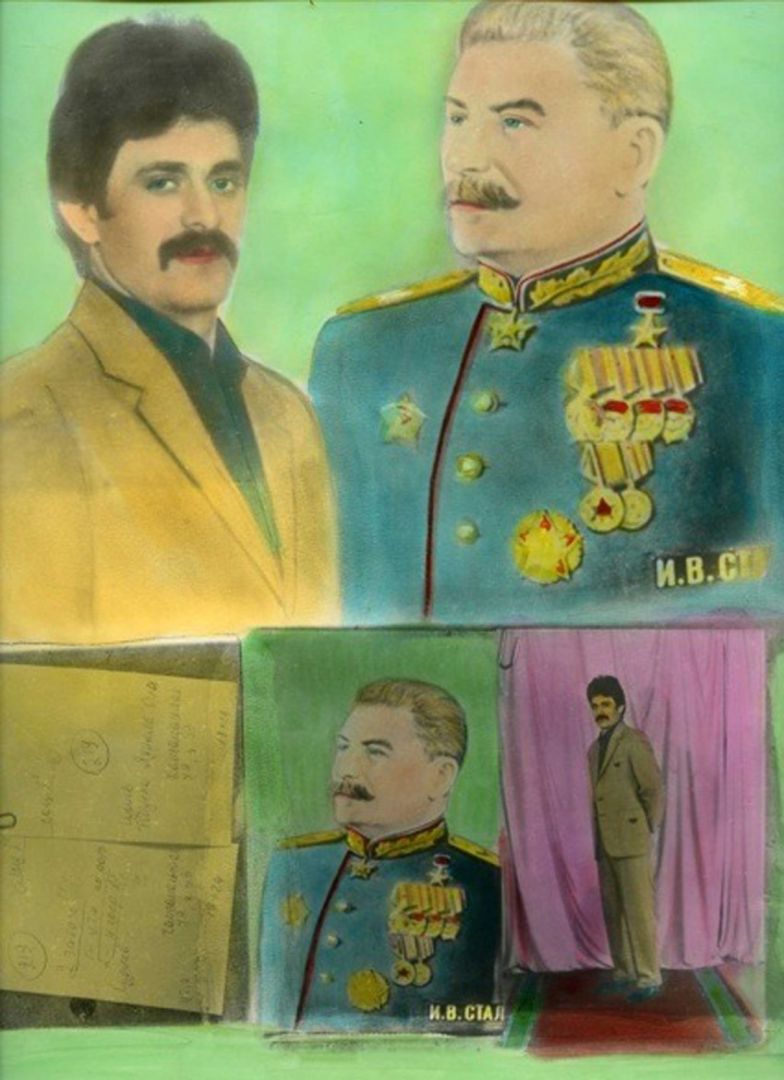

While Łódź had the Cinematic Form Workshop, in Kharkiv the Vremya group decided to break with obligatory social realism and propose their own understanding of photography, its subjects, and its tools. Their experiments with framing, lighting and color use served to develop their own representations of reality, the official images of which they rejected as ideological. Even if they showed universally known landscapes and figures, they either picked the objects and places that were not allowed to be photographed (as was the case with Boris Mikhailov’s Red Series, 1968—1975) or introduced points of view or compositions that would create an alternative to the conventional and schematic images disseminated in official media. They underscored the dissenting nature of their perspective with their techniques, which referenced avant-garde experiments (both cinematic and graphic) with editing and double exposure or resulted from their exploration of the limits of photography (using filters, colorization, negatives).

© Boris Mikhailov. Overlays, 1967. Courtesy of the artist

© Boris Mikhailov. From The Red Series, 1966. Courtesy of the artist

© Boris Mikhailov. From the Luriki series, 1971. Courtesy of the artist

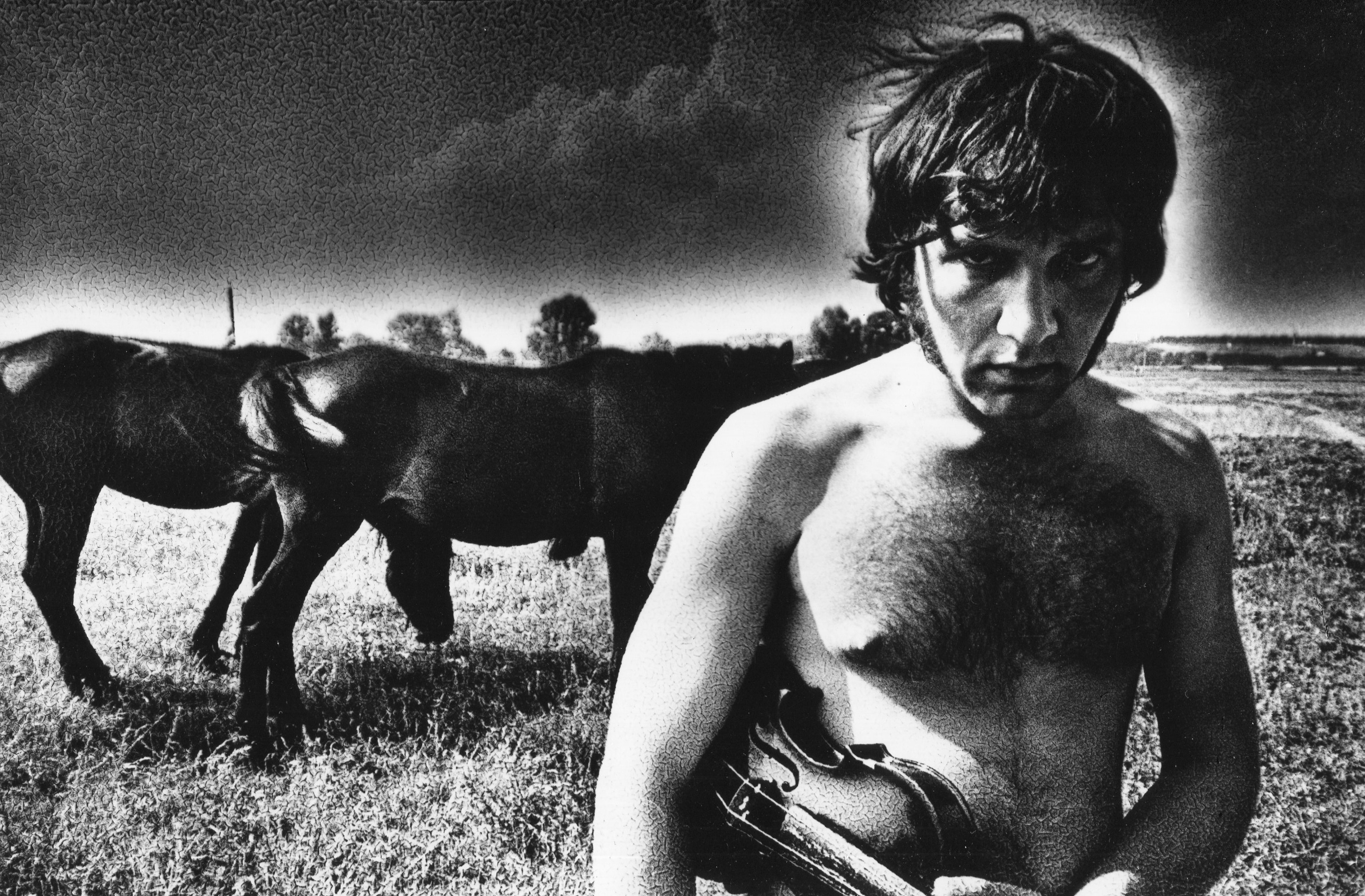

Their choice of means of expression corresponded with their selection of themes and subjects, which were frequently equally original. Black and white pictures of Evgeniy Pavlov from The Violin series (1972) show the figures of naked men whose images do not fall within the conventions of masculinity defined by its societal or state-mandated roles.

© Evgeniy Pavlov. From The Violin series, 1972. Courtesy Grynyov Art Collection

Pavlov paid no attention to uniform (military or civilian) which bestows rank upon its wearer, or the behavior associated with performing a particular function or profession. The young men photographed by him have been stripped of clothing, and at the same time set free from imposed norms of behavior and conventional imagery. The repeating violin motif becomes a pretext for composing male nudes which feature recognizable landscape elements — meadows, fields, a river, grazing horses. All these elements are combined to create a photographic impression that captures the unobvious relationships between the characters and an atmosphere of a time spent together.

© Evgeniy Pavlov. From The Violin series, 1972. Courtesy Grynyov Art Collection

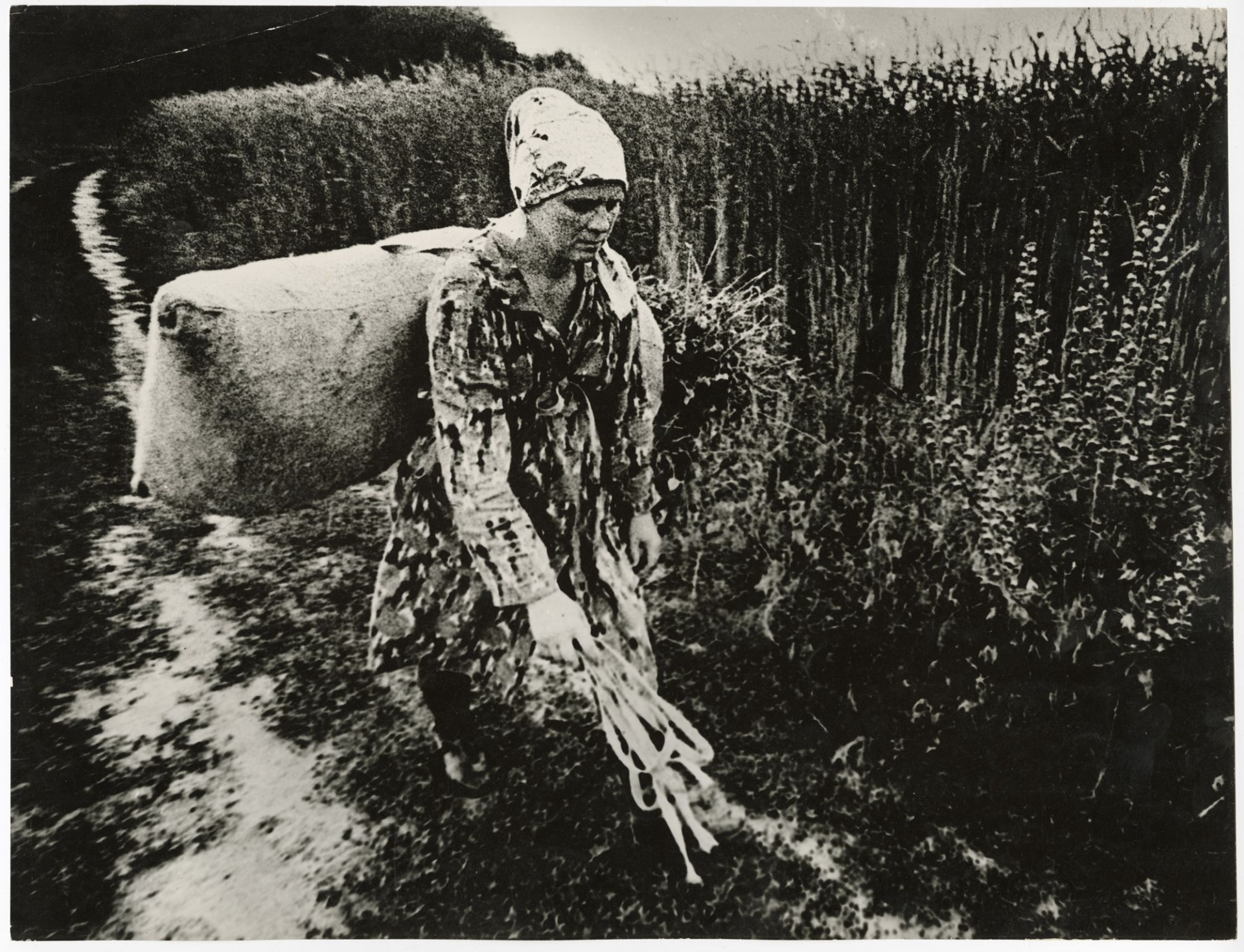

Anatoliy Makiyenko’s black and white photographs work in a similar fashion, centering figures which are unattractive and unimportant from the official propaganda’s point of view. The photograph Hard day (In the field, 1974) is a portrait of a woman tired from work, coming back home with a full sack on her back.

© Anatoliy Makiyenko. Hard day (In the field), 1974. MOKSOP collection

The photographed figure doesn’t strike any pose, and her downcast eyes lend the image an air of journalistic spontaneity and strip it of artificial heroization. The girl from the unassuming picture Dandelions (1974) also occupies the center of the frame. The picture was shot from up close, which results in the child’s petite frame nearly blending with the flowers in the meadow, and gives the scene a personal, intimate feel.

© Anatoliy Makiyenko. Dandelions, 1974. MOKSOP collection

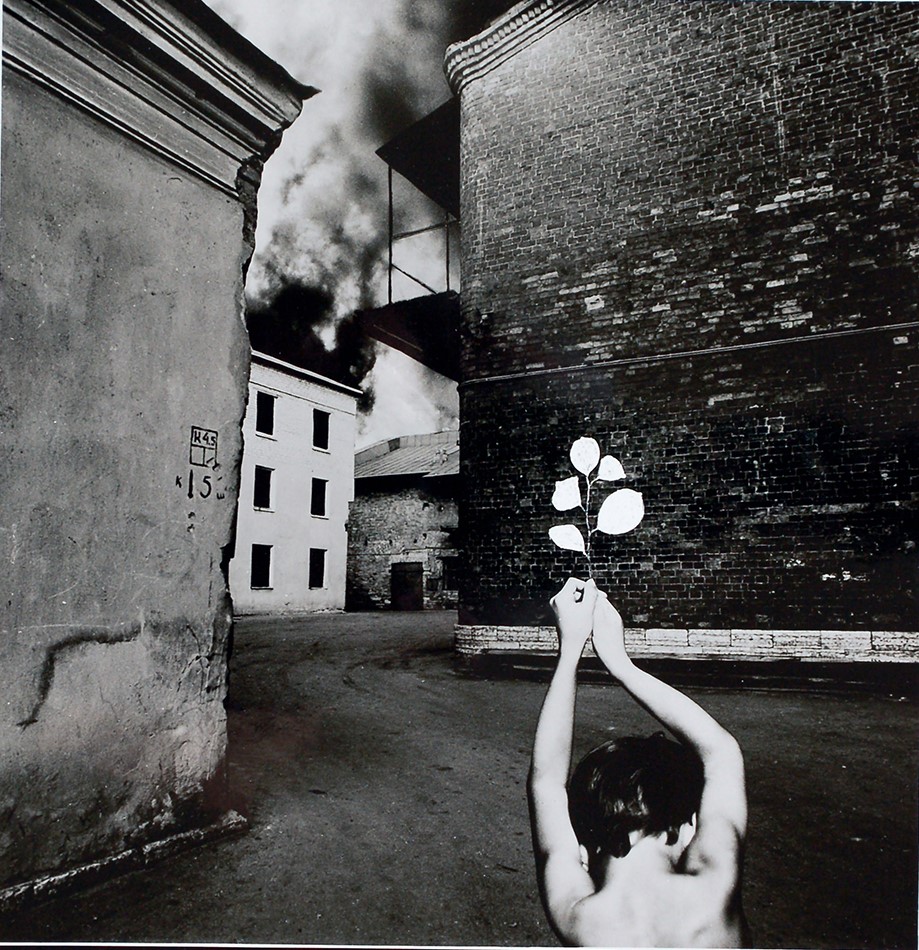

Figures photographed by Oleg Malyovany are also in the center of the frame, into which they have been spliced as part of collage composition. The collage technique serves two purposes in his work. Firstly, it allows him to construct a multi-layered visual message and, in the vein of avant-garde film editing, combine seemingly disparate elements to generate new meanings. Secondly, it gives the artist a dual role: that of the author of the used pictures, and that of the creator of the visual arrangement of multiple images. Maliovany inserts single, usually nude figures or their groups into everyday vistas — urban landscapes, nature, apartment blocks — breaking up their harmonious composition and opening up new avenues of interpretation. In his series Gravitаtion (1976), the nudes appear against the backdrop of a cobblestone street, suspended against the sky, or lying lost in empty space.

The photograph The Earth of People II (1977) uses a multiplied motif of high-rise buildings in which people turn into anonymous tenants locked in their apartments. However, here in windows, we see the nude figures of a man and a woman, and next to them — extended hands, which can be interpreted as gesturing defensively or desperately calling for help. Each of these images has a kind of dual dramaturgy — the first layer conjured by the photographed body and its expressive position, the second one created at the intersection of the individual elements of the composition, which either amplify or clash with each other, which is why the image requires focus and taking in the details and the whole simultaneously. This is best exemplified by Fire (1974) which uses three planes, giving the illusion of depth and perspective: in the background, there is a burning house, then we see the surrounding buildings, and it is only against this backdrop that a figure of a person holding a green branch appears. The exposition of these layered elements provokes a reflection on the creative nature of photography and its relationship with reality.

© Oleg Malyovany. Fire, 1974. MOKSOP collection

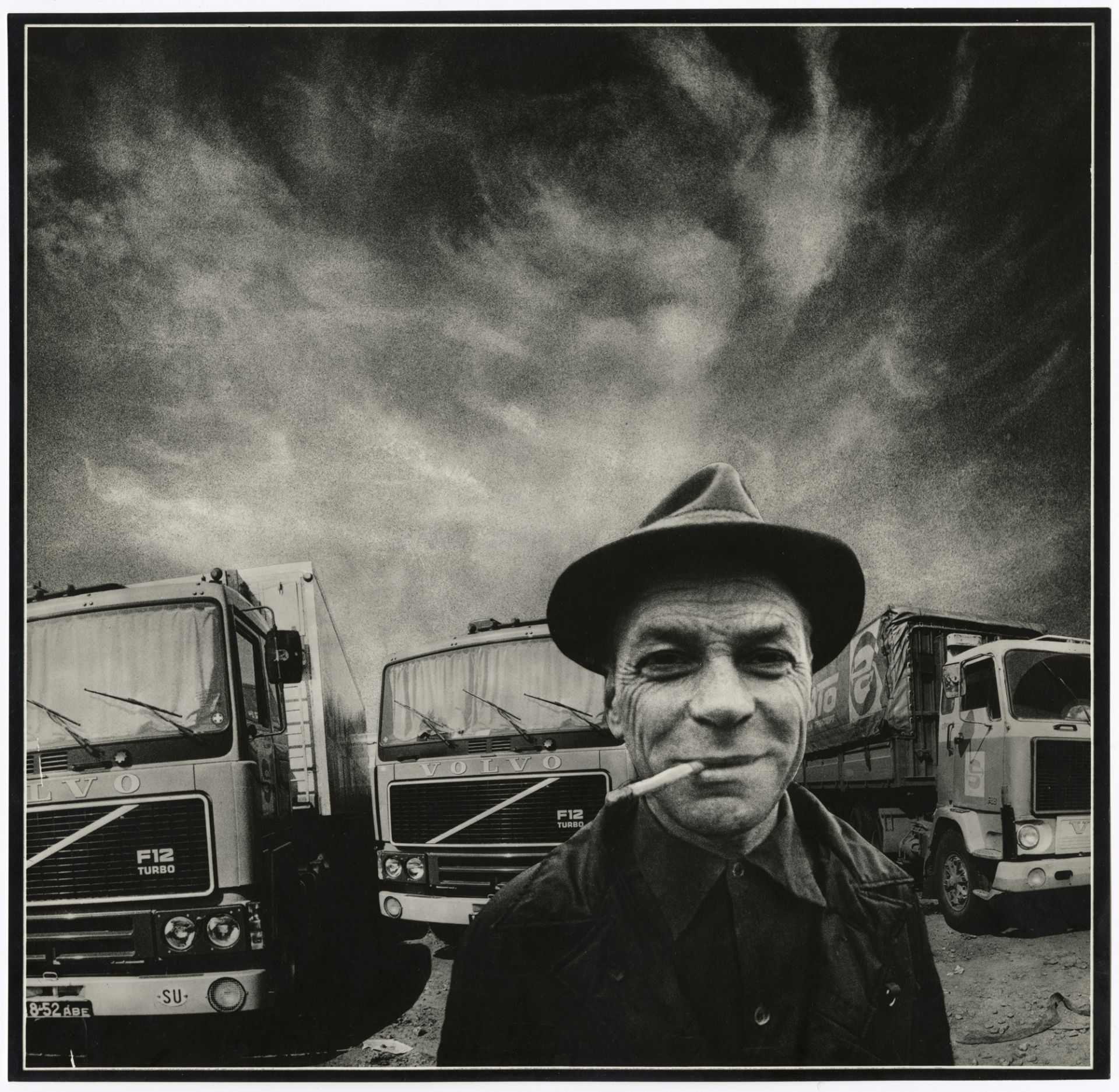

The collage compositions of Oleksandr Suprun, which bring to mind avant-garde experiments with form and perspective, focus our attention on the depth of composition. The technique of creating images from multiplied pictures combined at various angles allows the artist to transform, modify, and re-create photographic images of reality. This is evidenced by Suprun’s portraits of ordinary people at home or in farmland landscapes that were part of their upbringing. The people have been woven into the backgrounds in a way that makes their faces blend with the texture of walls or tilled fields as if their surroundings determined not only their lifestyle but also their appearance and character. The camera’s lens has been set up in a way that places the figures in front and center, properly exposed, even monumentalized by the worm’s eye view.

© Oleksandr Suprun. Stop on the Road, 1976. MOKSOP collection

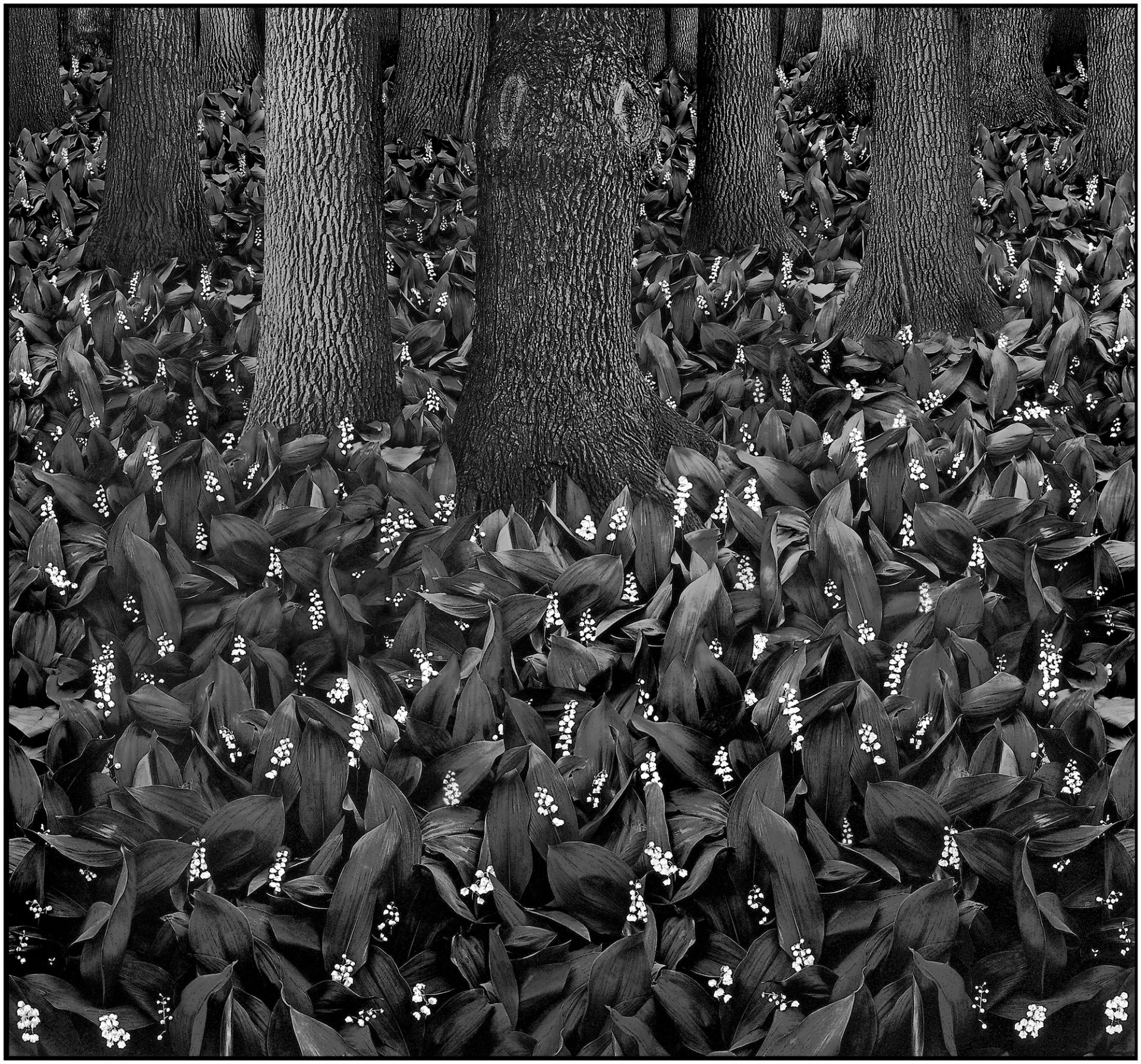

Meanwhile, the idea of mechanical reproduction of works of art, described by Walter Benjamin, is referenced by those of Suprun’s collages in which a single element is reproduced enough times to fill out the entire frame — as is the case with Spring in the Forest (1975). In the face of such treatment, photography’s claim to objectivity and authenticity is no longer valid, as it turns out that it can be manipulated — and even though in this case the intention was artistic, it might have just as well been political or ideological.

© Oleksandr Suprun. Spring in the Forest, 1975. MOKSOP collection

Therefore, if we were to try to find a common frame of reference for the work of photographers from Poland and the Ukrainian Soviet Republic in the 1970s and 1980s, we would have to take into account two issues. The first one is an attempt to create a kind of culture of resistance against the official model of visual culture and the poetics of representation — particularly in terms of people and the reality of their lives — through establishing artistic collectives that ensured mutual support and a kind of anti-ideological solidarity even if they didn’t aim to create a cohesive current or formation. The second question is related to artistic tools used, which were to serve experimentation with the camera and the image, shattering the transparency and neutrality of visual content, and exposing their creative nature.

The essay was written for the project "Kharkiv School of Photography: From Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics", which is implemented within the “Ukraine Everywhere” program of the Ukrainian Institute

Malgorzata Radkiewicz is an Associate Professor at the Institute of Audio Visual Arts at the Jagiellonian University (Cracow, Poland). Her work deals with issues of contemporary cinema and photography, analyzed in terms of critical theories: feminism, postcolonialism, posthumanism, and new materialism. She’s been particularly interested in the analysis of women’s expressions in film, photography, and arts, mostly in Poland and other East and Central European countries. She authored numerous articles in leading Polish film studies and cultural studies journals and texts published as chapters in collections of thematic essays on visual culture, including film and photography. She published a book on women filmmakers (2001), and another one on Polish cinema of the 1990s (2006), a monograph “Female Gaze: Film Theory and Practice of Women directors and artists” (2010), as well as books “Faces of queer cinema” (Oblicza kina queer, 2014), “Modern Women on Cinema” (Modernistki o kinie, 2016). In the years 2015—2018, she coordinated a research project on: “Pioneers with a camera. Women in cinema and photography in the Polish Galicia 1896—1945”.